Welcome to the third chapter of Mapping MAMM, an ongoing series diving behind the scenes of the Mapping Ann-Marie MacDonald Research Project. This week, I’ll get into how MAMM creates a pedagogically interesting and ethical work environment. For more information, you can read my first and second articles on the project.

If you’ve ever had the chance to work in a university environment, especially in research, you may have come up against the phrase “neoliberal academia.” Even if you haven’t heard of it specifically, you’ve likely worked in an environment where the rate of production is valued over your individual autonomy and health. Essentially, neoliberalism consists of increased marketization and an enormous focus on efficiency.

In academia, neoliberalism produces higher levels of competition among scholars; higher tuition fees for students due to the decrease in public funding; corporate management policies that emphasize efficiency and cost-cutting; and the commercialization of research, among other deficiencies.

“Most of the time, the Western way of understanding science is always obsessed with the product,” says Dr. Ebru Ustundag. “Most of the time, we don’t think about the process, the complexities of the research, the relationality of the research or the challenges of the research.”

In the Humanities, the competitive environment produces what Dr. Neta Gordon calls an “invisibilization” of labour as the discipline has “decided to value the single-authored monograph.” Oftentimes, the contributions of collaborators and student researchers are brushed aside to emphasize the research output. This assists projects in securing further funding but ultimately produces a harmful cycle.

The MAMM team is sick of that cycle.

As mentioned in the first installment of this series, MAMM was at least partially conceptualized as an opportunity for students to get paid. Now, three years later, it has grown and evolved into a workplace where student researchers not only get paid for their contributions but are acknowledged and credited for them.

Research Assistant (RA) Pilar Dietrich considers themself lucky, having gotten the opportunity to work in Dr. Julia Baird’s Water Resilience Lab before coming to the MAMM project.

In that lab, Pilar was given tasks and trained to complete them, but it was in the service of “someone else’s paper.” Pilar says it was a great introduction to academia and a “fantastic experience” where they learned valuable skills and practiced feminist ethics, but it was never about doing their own research. In Dr. Baird’s lab, RAs weren’t given as much ownership and there was a hierarchy dictating who did what work — a common practice in academia.

When they came to MAMM, there was a significant shift in the hierarchical approach to research: “MAMM, from day one, has felt like I have a hand in the pot,” says Pilar. “It feels like my research. And it doesn’t just feel like that, it just is like that.”

When I spoke to Pilar and two other MAMM RAs, Sloane Gray and Emily Mills, they used the example of the MAMM presentation Emily and Pilar gave at the Canadian Association of Geographers (CAG) Annual Conference, which received the award for Best Student Presentation.

“A common practice in academia [is] that the PI [Principal Investigator] gets first author. That’s not the case here,” says Pilar. “The case here is that whoever does the brunt of the work gets those full author names, and then everyone else gets credited as co-authors, as co-labmates and co-researchers, which, once again, sets us up for success in graduate school.”

MAMM’s ethics of care go beyond accreditation; they are present in the work environment itself. RAs are valued and paid for the time and effort they put into MAMM, whether that’s collecting data, preparing presentations or spending 40 hours reading and analyzing an 850-page novel like The Way the Crow Flies. MAMM students aren’t pressured by constant deadlines, steady outputs or hourly quotas; instead, they are encouraged to take care of themselves and work together.

“We value slow scholarship,” says Emily, “because to do feminist work, you can’t be rushing, because then you’re not listening.”

It helps that the project is funded by a sizeable Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Insight Development Grant, which the RAs attribute as one of the main reasons they can commit to this type of scholarship at all.

It’s not all about luck, as Dr. Aaron Mauro explains: “Digital Humanities work tends to be funded quite readily because of the public-facing nature of it. It’s engaged. It’s meant to be shared broadly. It’s not something that is hidden in a university library or in an academic journal.”

MAMM’s ethical, open nature is not only a way of circumventing and resisting the oppressive qualities of the neoliberal system, but a legitimate, alternative system within itself. As Emily says, they’re “[imagining] a new way of doing academic work.”

“We’re trying to foster a community that supports each other,” says Sloane. “And I feel like those very neoliberal, output-oriented, deadline-specific, efficiency-prioritizing research methodologies just don’t work when you’re trying to build a compassionate community of researchers.”

It’s easy to presume that a lack of deadlines means a lack of structure, but Neta sees it as completely the opposite:

“It’s like a really, really good improv game where you need very strict parameters. You need someone who’s [on] the outside saying, ‘These are the rules of the game.’ And they’re strict. And you have to follow them. But once you have those parameters in place, everything inside is just play. And we’ll see what emerges. […] Whatever happens inside, that’s where the knowledge production is happening — that’s where the surprising stuff is happening.”

And it’s obviously working.

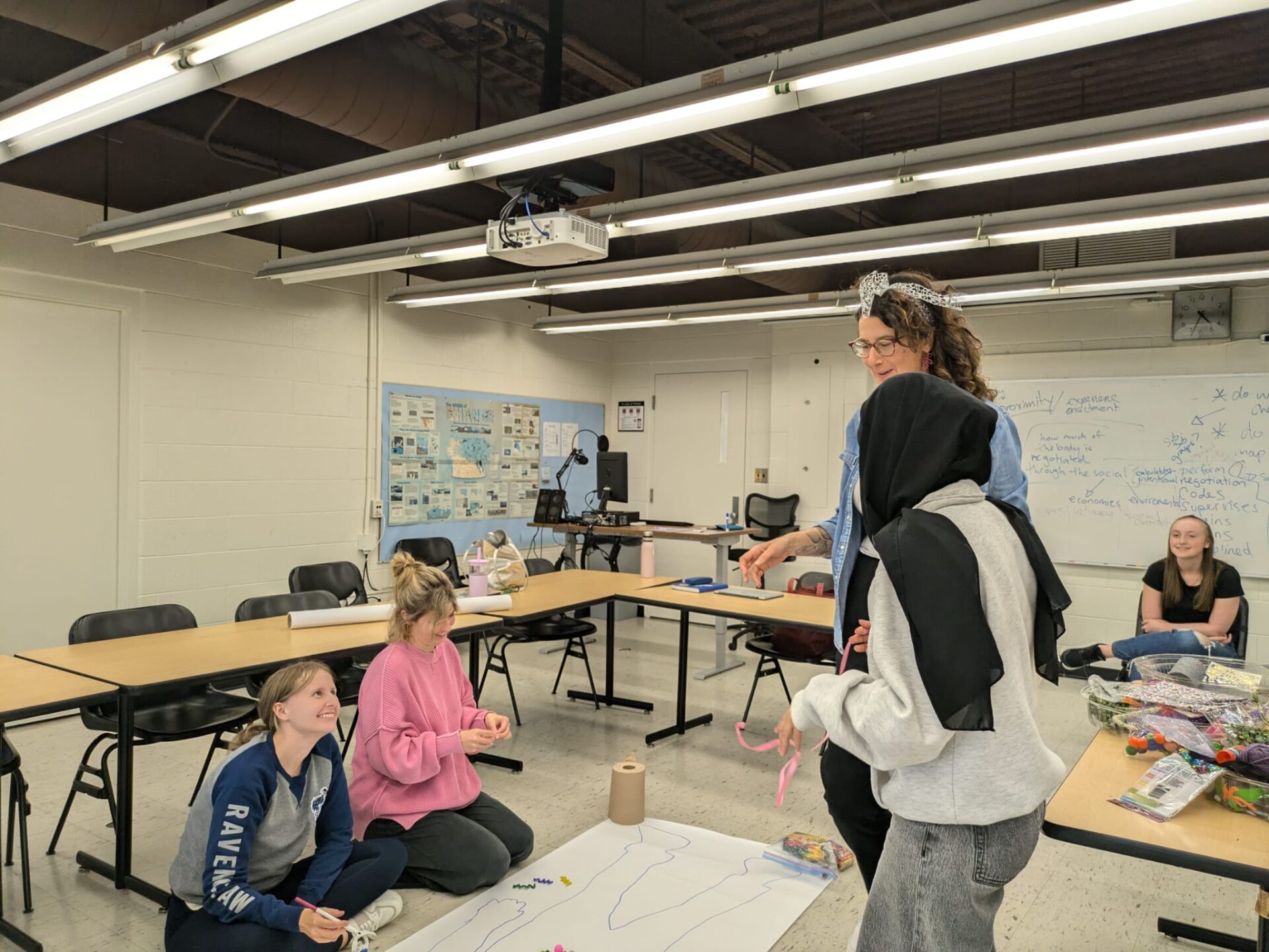

These students — from what I’ve seen and learned from them — are thoughtful, well-spoken and incredibly intelligent. They recognize the uniqueness of MAMM’s pedagogy and are clearly passionate about preserving it by sharing their experiences at events like the ESA Undergraduate Conference. My main takeaway from that presentation was that these are students who feel seen in the academic workplace; who are blown away by the dissolution of strict hierarchies and want as many people as possible to know that this is a different, viable method of research.

Dr. Ustundag calls the relationship between students and professors within MAMM a different type of “mentorship” — one which focuses on “professionalization” in the academic world.

“There is so much negative discourse about the young generation,” says Ebru. “And I’m like, ‘Absolutely not.’ I have seen with this project how this generation actually knows how to hold spaces and communicate so beautifully.”

People tend to call my generation “lazy” or “incapable,” but perhaps the problem comes from trying to fit my generation into the cramped spaces that caused so many problems in the first place.

MAMM is an excellent example: Sloane entered the project when he was in the first semester of his first year, and despite not knowing anything about Ann-Marie MacDonald or geography at the time, he became a pro at transcribing her archival materials and has since learned how to do “a little bit of everything.”

The Brock Press is another great example. Despite a lack of faith from certain parties, this paper has shown that it can thrive without any external influence in its business or editorial affairs — that it is at its absolute strongest when it is entirely by and for the students of Brock University.

“Even in my first year going into [MAMM], I felt like what I was doing […] mattered,” says Sloane. “When we were doing all of this work with the metadata, there wasn’t anybody actively overseeing every single thing we did all of the time. They trusted us. We learned what we had to do, and they trusted us to do it properly.”

The professors at MAMM not only know their RAs can do the work, but they also trust them to do it. And ultimately, giving this much responsibility to students only produces positive outcomes. Instead of being stressed and pressured to be the best all on their own, MAMM’s RAs are encouraged to lean on each other and ask for help or guidance when they need it.

“It’s normal to not be in your element,” says Sloane. “You shouldn’t be in your element all the time. That’s the nature of an interdisciplinary project, is that it’s not always going to be your turn.”

Thus is the nature of learning, is it not? Even professors are usually only specialists in one field, and anyone, if given the space to do so, can have insights into topics they aren’t experts in. The important thing is that nobody is ever made to feel stupid — questions are not only encouraged, but necessary for knowledge to be produced.

“If someone is claiming to be a singular disciplinary expert, then they’ve maybe missed some questions,” says Dr. Mauro. “I think that just by virtue of our interconnectivity and the way that we share our work, it means that we have a plurality of audiences, we have a plurality of collaborators, and so we have a plurality of disciplines.”

In Humanities spaces, one of the most frequently used phrases revolves around “form reflecting content,” meaning that the physical composition of a text mirrors the subject matter it’s trying to portray.

With MAMM, this is absolutely the case, and when I had the opportunity to speak to the brilliant Ann-Marie MacDonald herself, this became unmistakably evident.

Ann-Marie says she is “so impressed” by the way Neta leads the MAMM team: “This is a really smart, dynamic person whose values are in line with my own.”

She compared MAMM’s research work to a “medieval or Renaissance mural”: a collaborative and artistic endeavour — not only among researchers but a form of public scholarship — that feels “refreshing” to her.

“I try to bring worlds together,” says Ann-Marie, and MAMM’s interdisciplinary study, which spans across fields of learning, art and expression, is “just another way of telling a story.”

Ann-Marie’s work is inherently collaborative and human, emphasizing friendship and relationality even when her stories become “miserable,” as Sloane puts it. The feminist ideologies in Ann-Marie’s work — the content, if you would — are then perfectly mirrored in MAMM’s form.

This is an environment that produces “the compulsion to act in excess for each other,” as Sloane so wonderfully puts it.

“It’s very easy to want to be a feminist,” says Pilar. “[But] it’s very challenging to enact it when the systems are against you.”

Despite operating at a level beyond the confines of traditional, neoliberal academics, MAMM has found a way to still engage with the field, still present at conferences, still produce papers and still receive recognition for the work they’re doing within this new pedagogical framework.

Ann-Marie says it’s “immense” that MAMM’s framework reflects the feminist ideals of her work, especially today. Every few years, there’s a flare in misogyny: misogynistic jokes sneak back into the colloquium, says Ann-Marie, such as calling someone a Karen. “[It’s like saying] this kind of woman is okay, [but] that kind is not okay.”

When Ann-Marie was young, she tells me, she used to be embarrassed when her Lebanese mother would call things out to get her money’s worth or get things the way she wanted. Now, she knows that her previous mentality was a by-product of the “subtle signs that keep women in their place.” She says she gets disappointed when she sees young people being pushed over, and that being confrontational isn’t a bad thing.

Being assertive and fighting for what you want is the conduit for revolution, after all. It’s part of the fight for equality and fair treatment of all, regardless of gender, race or age.

I hope I’ve shown you that MAMM, too, has proven itself to be a conduit for change, particularly in the treatment of young people in academia.

It’s inspiring, to say the least.

“This lab feels to me like a community, and that’s intentional,” says Pilar. “That’s not an accident. You don’t create a community by accident. It’s impossible. […] I have been stressed about school, I have been stressed about other work, [but] I don’t stress about MAMM. I don’t stress about it because the environment that we’ve built is incredible.”

The Mapping Ann-Marie MacDonald Research Project is a promising model not only for other Humanities-based research projects, but for projects of all sorts of disciplines, especially in the university setting.

This subject of community will be one I return to in the fifth installment of the series, but first, I’ll be taking a short detour into the realm of Canadian Literature.

That will be next week, but until then, remember to resist oppression whenever you can, and, as Margaret Mead wrote, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.”

Disclaimer: As an RA employed by MAMM and Brock University, I was paid to write this series; however, my compensation was not accompanied by any assertions of bias or censorship, and the views expressed in these articles, aside from quoted material, are uniquely my own.