Mapping MAMM is an ongoing series which gets into the research questions surrounding the Mapping Ann-Marie MacDonald Research Project. My previous articles have introduced the project as well as examined its cross-disciplinarity and ethics of care. In this fourth installment, I’ll get into the “fraught construct” that is CanLit.

At first glance, Canadian literature seems a relatively simple term to understand. It’s just “Canadian” literature, right?

Well, it’s actually a bit more complicated than that.

As I conducted my research into MAMM and its complexities, I began to doubt that such a thing as a “Canadian” literature existed at all. If “CanLit” is a genre we can study in university the same way we might study “Gothic” or “dramatic” literature, then how do we determine what constitutes something as “Canadian?” How is it that some authors are defined by their Canadianness while others seem to transcend these national barriers and exist beyond CanLit?

Dr. Ebru Ustundag uses the example of Margaret Atwood: “Margaret Atwood kind of crossed the borders, crossed the nations, but it seems that Ann-Marie MacDonald is always presented as the Canadian.”

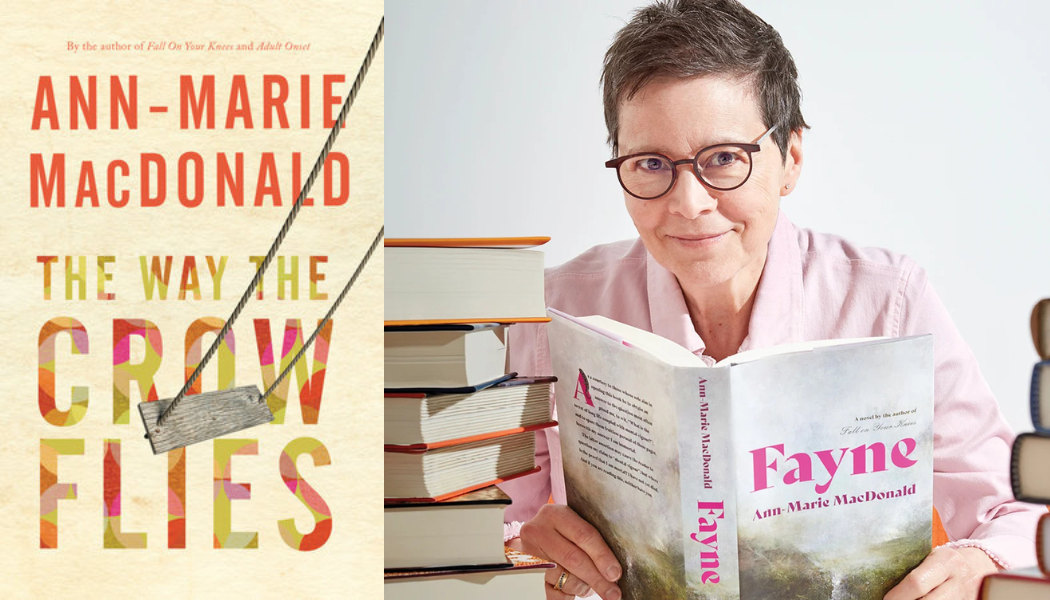

She used the example of a conference she attended in Santa Fe, where — despite Ann-Marie MacDonald’s legendary status in Canada — many of the American English professors had no idea who she was. Unfortunately, while Ann-Marie’s first novel Fall on Your Knees was hugely popular in the U.S. — being one of the only two Canadian novels to be selected by Oprah Winfrey for her book club — her latest novel Fayne was not published in the U.S. because, as Ann-Marie puts it: “at 722 pages, it is my longest book and it was, indeed, deemed too long and too queer by U.S. publishers.”

Studying Ann-Marie MacDonald invites a conversation about national identity and the politics of geographical space. Ebru is “critical about the boundaries” and calls borders a “fiction.” Especially when considering the current fraught relationship between Canada and the United States, Ebru thinks it astounding that someone could claim they will never cross the border when all that constitutes that border is a line on a map.

After all, Canadian stories and issues aren’t only pertinent to Canadian people.

But even within the country, identifying a singular “Canadian” literature is difficult, if not impossible, says Dr. Aaron Mauro: “We as a nation have always struggled with defining a national literature, partly because we are a nation of immigrants on colonial territory.”

However, Aaron considers this struggle a strength of CanLit, which “builds not the unified singular Canadian literary culture, but a disparate, overlapping set of territories.” He considers MAMM a Canadian project “in the sense that it’s shy about being overtly nationalistic or patriotic; that instead, our strengths come from having our sense of identity be a little more fluid and admit that it’s more multiple than […] a singular national identity would allow.”

In this sense, Ann-Marie MacDonald, who calls herself a “major Canadian inclusivist,” is a perfect focal point for the study of Canadian Literature.

RA Pilar Dietrich confesses that nationalism “scares” them; that the recent surge in Canadian patriotism is a practice of dividing people into an “us” and an “other.” It is this kind of thinking that expands political gaps and produces the kind of exclusionary, discriminatory practices that we’re seeing right now in North America, after all.

However, studying someone like Ann-Marie MacDonald, whom Aaron calls a “luminary of Canadian media,” expands the conversation about who is and who should be included within a national identity such as ours.

“We are studying Canadian literature, and Ann-Marie MacDonald specifically within the Canadian canon, because Ann-Marie MacDonald includes a lot more people in us than a lot of Canadian authors,” explains Pilar. “There’s a lot more nuance of who can be Canadian and what type of stories Canadians can tell.”

Ann-Marie’s us contains people across various identities: people who are lesbian, who are intersex, who are refugees and much more. Indeed, as she tells me herself, what makes a story “Canadian” should be a “very broad designation” and constantly “evolving.”

“It’s very important to acknowledge that we do have a national body of work,” says Ann-Marie. “Let’s own it. Let’s be proud of it. […] You only keep it alive by returning to it and talking about it and disagreeing.”

CanLit is broad, she says, but it’s worth tackling and exploring how Canadians tell stories differently from other countries and cultures.

Dr. Neta Gordon calls Canada and the Canadian identity a “fraught construct.” Still, she says there’s something “distinctive about literature that produces […] a recognition of home,” even if that’s “always a kind of skewed recognition.”

“Canada is a fraught construct, but it’s a construct that defines lives,” says Neta, “and it defines the lives of the students who are here and defines the lives of their neighbours and their families,” so studying that construct, even if it’s imperfect, is “ethically important, […] exciting and emotionally resonant.”

As a Canadian writer, there’s no escaping CanLit. This used to scare me — “What if it constricts my abilities as an artist,” I used to think to myself — but the more I’ve studied MAMM, the more I’ve realized that CanLit isn’t a genre: it’s a distinction.

“I feel really lucky to be a Canadian,” says Ann-Marie.

CanLit doesn’t limit the prolific Ann-Marie MacDonald; it gives her a platform to share a plethora of stories and voices. You shouldn’t be afraid of telling the wrong stories or of telling stories wrong, says Ann-Marie, because someone is going to find a reason to get upset either way. As a writer, you just need to plunge in. Experiences are transferable, and “there are so many ways in which we are all in this together.”

The people at MAMM understand this as well.

“What we’re discovering is that it is an international story,” says Aaron. “That while studying a single author, we’re seeing a range of perspectives being brought in, and I think that that is something that is quintessentially Canadian, in the way that it is so open and separate from a singular notion of Canadian identity, and that’s been really gratifying for us to see.”

Like we’ve discovered previously, MAMM is not about any singular perspective. As a project with roots in the Digital Humanities and operated in line with feminist ethics of care, it is intrinsically concerned with the plurality of voices and tools and ideas, much like Canada and its national body of literature.

Once again, we see form reflecting content.

The layers of collaboration which constitute the Mapping Ann-Marie MacDonald Research Project run deep — much deeper than I realized when I started this series. Teamwork is in MAMM’s DNA, from the way it invites collaboration among disciplines, among professors and students and among Canadians writ large.

But there’s one more relationship I haven’t fully explored, and that’s between the researchers and Ann-Marie MacDonald herself. Next week, to cap off my little series, I’ll discuss their unique relationship and what it means for the world of academia.

Until then, remember to be compassionate. You are only one person, and your opinion isn’t the only one that matters. Take a moment to consider other people’s perspectives and make the effort to be a better neighbour in your community.

Disclaimer: As an RA employed by MAMM and Brock University, I was paid to write this series; however, my compensation was not accompanied by any assertions of bias or censorship, and the views expressed in these articles, aside from quoted material, are uniquely my own.