*DISCLAIMER: Reach out to a healthcare professional for a proper diagnosis, or for professional help. This is intended to be educational information, and should not be taken as medical advice.*

Modern therapy has its limits.

Here in the West, we put a huge premium on happiness. We are inundated with messaging that tells us to not only be happy but be uniquely happy, find a happiness that’s yours. What if the reality of these items, happiness and uniqueness, were that they are mutually exclusive? In other words, what if those things that make us unique are those things we’re willing to suffer for, those things that we are willing to be caught in that creative fever that goes beyond the pleasure principle to realize?

This is not a prescription for an atavistic asceticism, something that has ironically emerged as a subspecies of the self-help industry in the form of boiled down, cleanly packaged revivals of ancient philosophical schools such as stoicism. Instead, what if we risk the theory that parsing these categories of happiness alongside uniqueness and self-acceptance, exposing their immanent contradiction, can go a long way when it comes to finding deep satisfaction?

In fact, this ideological split happened institutionally in the mid-20th century when the interdisciplinary field of psychoanalysis birthed and began splitting from the then new, specialised field of ego psychology which offered a positivist account of the ego, looking to study and remedy it as an empirical phenomenon.

Arguably the most famous Freudian disciple still being used in 21st century social theory, Jacques Lacan, was not excited about this emerging new science, calling American ego psychology a “judicial astrology” full of “philistines,” and that it “immerses its categories in psychoanalysis to reinvigorate its lowly purpose of social exploitation.”

After fully shedding the vestiges of psychoanalytic treatment, save the general acceptance of the unconscious, ego psychology has come to dominate therapeutic treatment today, and with its criterion of “the unity of the subject” (Lacan) it fits nicely with the massive pharmaceutical companies that make a killing by solving psychic issues through a one-to-one treatment of psychic distress with different medications. However, we should problematize this simple reduction as Mark Fisher, a man who struggled with major depression, so presciently did in Capitalist Realism:

“The current ruling ontology denies any possibility of a social causation of mental illness. The chemico-biologization of mental illness is of course strictly commensurate with its depoliticization. Considering mental illness an individual chemico-biological problem has enormous benefits for capitalism. First, it reinforces Capital’s drive towards atomistic individualization (you are sick because of your brain chemistry). Second, it provides an enormously lucrative market in which multinational pharmaceutical companies can peddle their pharmaceuticals (we can cure you with our SSRIs). It goes without saying that all mental illnesses are neurologically instantiated, but this says nothing about their causation. If it is true, for instance, that depression is constituted by low serotonin levels, what still needs to be explained is why particular individuals have low levels of serotonin. This requires a social and political explanation; and the task of repoliticizing mental illness is an urgent one if the left wants to challenge capitalist realism.”

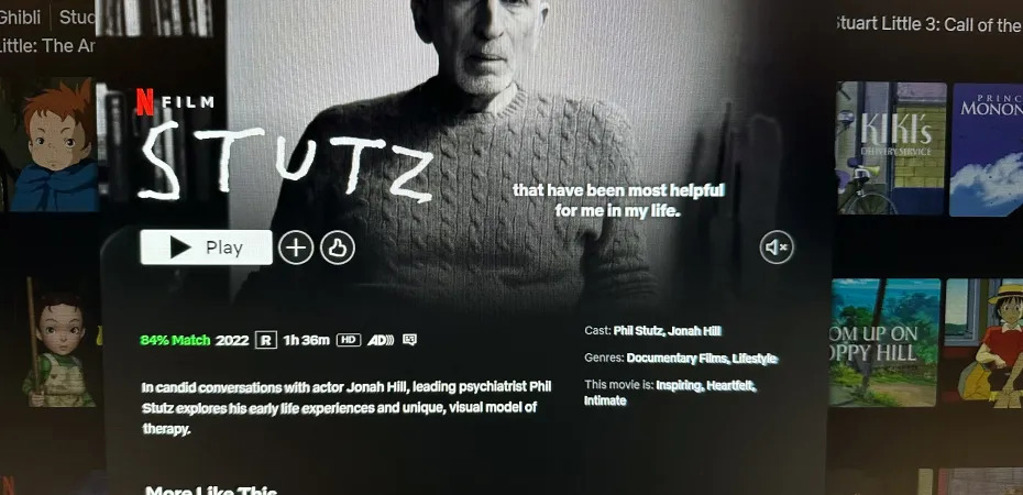

To explore this contradiction of happiness and self-acceptance with a current example, I’m going to put Lacanian categories of analytic treatment in conversation with actor Jonah Hill’s recent documentary on Netflix titled Stutz.

Stutz is a good example of how a lot of ego psychology operates today. Phil Stutz, Hill’s therapist and object for the documentary, preaches a frank and straightforward approach to therapy, though it should be said that his brand of therapy is unique in that he mixes Jungian mysticism with more modern cognitive behavioural therapy. This is something of a perfect combination given our ruling postmodern ideology where we adopt cheapened eastern spiritualism, as well as playful sympathies to astrology and other cheap metaphysics, while staying anxiously grounded by a good liberal instinct to adhere to scientific technocracy.

Hill is clearly ecstatic about Stutz and his approach throughout the documentary; in fact, one gets the impression that Hill reveres his therapist. Stutz seems to grasp this as well, often deflecting or probing Hill’s admiration of him, up to a point. This is precisely where Lacanian analysis would read the Hill-Stutz therapeutic journey as having made progress but remaining ultimately incomplete.

At the end of the documentary in an admittedly touching scene Stutz says to Hill that he “feels closer to him now than when we started” and tells Hill “I love you,” Hill replies, “I love you” — the screen goes black and credits roll.

Sigmund Freud was explicit, in a letter to his disciple Carl Jung, that psychoanalysis is “in essence a cure through love.”

The Lacanian approach also expects the analysand (Hill) to love their analyst (Stutz). In fact, Lacan believed that every speech act, precisely as a speech act, is an implicit demand for love. However, the Lacanian analytic experience takes a radical approach with this knowledge: the point is for the analysand to not demand the love of the analyst anymore, to be fully self-sufficient. Put in Lacanian jargon, the point is to be able to incarnate the big Other (with a capital “O”) — law, language, radical alterity, trans-individual authority — into oneself, to have one’s own symbolic compass if you will.

The Lacanian cure has the analysand finally not idealizing the analyst, no longer seeing them as the locus of truth (the big Other), not feeling a parental-like bond with the analyst anymore. Only then, as Lacan says in the final page of his famous Seminar XI, does “love beyond Law” emerge, no longer as narcissistic (mis)recognition, but as a feminine, asexual sublimation of the Thing — experienced in the “ecstatic surrendered” of music and religion as Bruce Fink explains — from drive into love.

The problem with modern ego psychology is that it’s more lucrative to be this friend(ly master) who embodies truth for the analysand because it remains utterly positive, it wants to assure the subject of the unity of herself, and so therapist after therapist will lend their subjects Mark Manson’s The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck and ask how that new medication is working until the cows come home, but their intervention never traverses beyond this stage. The Lacanian solution is that no unity of yourself exists; we are split subjects, divided by the effects of language which turn our needs into demands for love, demands which always miss the mark. This not hitting the mark is where desire enters the picture, because in order to desire something we must not have it. If we have what we desire, we thereby can no longer desire it.

Desire is founded around a lack.

Lacan puts it in this way: “Desire is neither the appetite for satisfaction nor the demand for love, but the difference that results from the subtraction of the first from the second, the very phenomenon of their splitting (Spaltung).”

So when we are encouraged to find happiness in our uniqueness in much of the therapeutic and advertising language that permeates discourses in the West as well as in modern approaches to therapy — we should question whether there is a stable possibility for both at once.

Perhaps the most spiritually fulfilling situation to be in is to suffer for oneself by fully assuming one’s division.