**Disclaimer: This article deals with topics surrounding violent sexual assault**

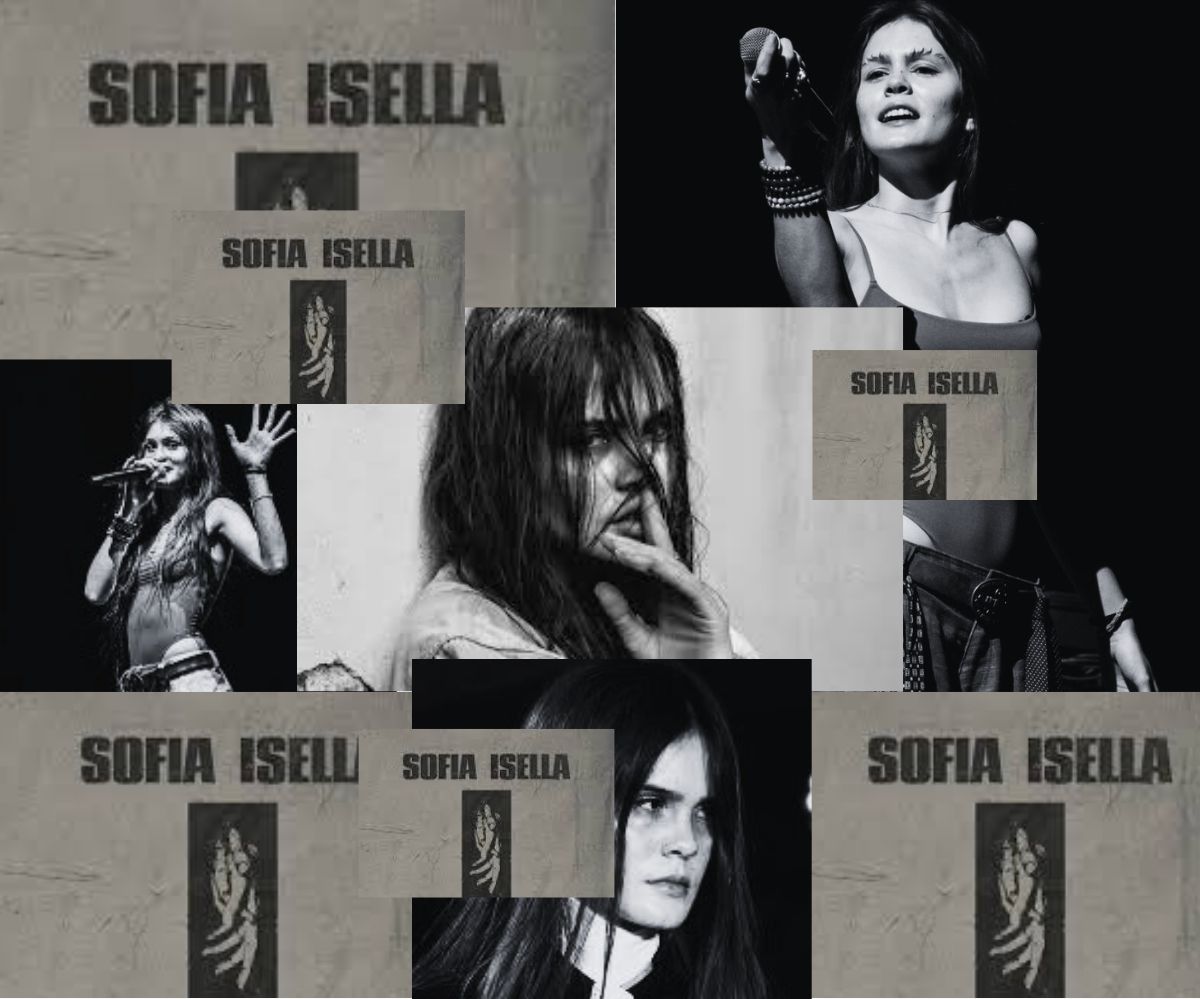

19-year-old singer/songwriter Sofia Isella has opened for more well-known artists like Taylor Swift, but as an independent artist, she is completely underrated and deserves to be recognized for her provocative feminist music.

Sofia Isella opened for Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour in London 2024, as well as for Melanie Martinez and Tom Odell. Her most popular video on YouTube has over 1.3 million views.

Her songs are deeply satirical, provocative and poetic. Let’s look at some of my favourite songs of hers and analyze what makes them so ground-breaking.

“Everybody Supports Women”

This song is all about the societal hypocrisy surrounding women’s empowerment and explores internalized misogyny.

The first line begins with the statement that “everybody supports women until a woman’s doing better than you,” suggesting that one’s support is conditional to their own success. Isella goes on to claim: “Everybody wants you to love yourself until you actually do.” Here, she points out how our society emphasizes self-love and confidence, but anything beyond striving for it — like actually loving yourself — is seen as overconfident, self-indulged, selfish and unattractive.

The lyrics then delve into criticism and envy: “It was something about her hair, so perfectly fallen, / she was nice and smart and funny and got everything she wanted.” This line portrays a woman who is beautiful, intelligent, humourous and successful, using these traits to explain why the speaker hates this woman. She becomes a target of scorn, resentment and obsession, evidenced by the speaker’s lack of pause and breathless voice. In the same breath, Sofia Isella goes on to say: “And she does charity, isn’t that the most obnoxious thing you’ve heard? / Her popularity, she’s too pretty for her own good / She’s probably self-centred, we hate her and she’s nothing / If everybody leaves her, then she had it coming.” The woman’s charitable actions are labelled as obnoxious and her popularity is viewed negatively, as if she’s a Mean Girl (because of the stereotype that popular people are mean, ruthless, fake or plastic). The narrative emphasizes how society can twist positive attributes into reasons for hatred, especially when a woman succeeds in “having it all.”

In a quick statement reminiscent of slam poetry, the speaker insists: “I would like it to be known that I’m not like her / I’m mocking her ’cause I’m not like her / I’m not like those girls who are not like those girls / I love doing makeup, I don’t mock women like her, I’m not like her!” The contradiction about mocking whilst not mocking displays the contradictory social hypocrisy that the song is all about. Women in society claim to be supportive but at the same time want to be different and ultimately better than each other. To mock another woman can be seen as either humorous or mean depending on the circumstances, so the speaker saying she both mocks and doesn’t mock “women like her” shows that she’s very conscious about this double standard in the misogynistic society she lives in.

The song talks about success and ambition as if the object of affection or scorn is a storybook character; a woman could easily be the Evil Queen or Snow White depending on her confidence or arrogance.

Many women, for example, disdain Taylor Swift simply because of her popularity: they say she’s overrated. But I think a lot of people don’t like Taylor Swift because of her seemingly perfect life, talent, looks and success. They can’t help but engage in “sisterhood sabotage” because of internalized and competitive misogyny.

The song views ambition as something that is acceptable, admirable or “swallowable” if you tell the story right: “Say that you hate yourself and self-criticize / But if we smell desperation on your neck and face / We’ll drag you across your own public stage.”

A woman appearing too confident or being too vocal about her success can make her seem “desperate,” the song suggests. If women don’t self-criticize or put themselves down in some way, they are viewed like the Evil Queen in Snow White: full of themselves, hungry for fame and ultimately unlikeable.

The speaker discredits a successful woman out of envy, burning “anything with her name attached” simply because of what “her name” has come to represent to a competitive and misogynistic society: a threat, a reminder of their own flaws and a slap in the face.

“What a waste! / What a shame! / I was starting to like her, but now she got great / We’d never hate her to her face, / but I hope she knows! / SHE KNOWS!”

Near the end, the speaker admits that she hates her: “’Cause staring at her too long made our life look like muted pastels / We’ll love you if you just make us feel better about ourselves.” Hating someone else for their accomplishments is often about internalized insecurities. Famous people are often objects of scorn because of how they make us feel about ourselves, and women are particularly prone to comparing themselves to other women. The song suggests a dynamic where women feel pressured to compete, putting each other down instead of supporting one another while spurred on by a culture of toxic comparison.

“Us and Pigs”

This song uses Juvenalian satire (a more serious, dark type of satire) to emphasize society’s view of women. “Us and Pigs” begins with the female speaker at a dinner party with “beasts” who look at her body like it’s food. From this point on, the speaker addresses the beasts as “you,” which shifts the song to a more accusatory tone. The lines, “You ask, ‘What’s the special occasion?’ / Like I dress and dance just for you,” refer to the idea of the male gaze and some men’s assumptions that a woman is dressing and really existing “for them”: either to provoke, entice or seduce them. Why else would women exist if not for men, right?

Isella then begins to question the feigned ignorance of people: “Our women are cattle there’s blood on our kids / Are you being paid to not pay attention? / Does it have to happen to your mother / your sister or your daughter for you to take it personal?”

What follows is a long, melancholic moan, resembling a howl, before Isella goes straight for the throat: “So pump us full of sperm, put us in a barn, / us and pigs on a Mississippi farm / In nine months we’ll have a kid you won’t care about / And if the kid’s not straight, White and male, / we guarantee a living hell; murder in the name of a loving God!” The moan then resumes, this time echoing and almost sounding like the cries of women in a large barn, treated like cattle. The idea of a “merciful” killing is also mentioned, as if it’s better to “put down” a female or non-White baby rather than letting them suffer their whole lives, being treated as less than human.

The lines, “I guess we were just being a little loud / Shut us up and put apples in our mouths,” further connect women to animals like pigs, who are constantly bred and eaten but useful for little else. Finally, the line, “but pull your own daughter out from the lineup,” shows the hypocrisy that was mentioned at the beginning (“are you being paid to not pay attention?”).

“Us and Pigs” is one of Isella’s darker pieces, but as we’ll see, it’s not the only one. Be advised that this next song makes direct references to rape.

The Doll People

The “doll people” that this song speaks about are women, and it’s another Juvenalian satire on the male gaze: “The doll people are not men / They are made of ass and glass / […] / W are statues with a pulse / We are art you can f*ck.” Despite being literally called “people,” the doll people are seen as pretty objects, playthings and things for men to look at and enjoy. It makes sense then that “the doll people are quiet / What is there to say? Art does not interpret itself / There are men with a day to save.”

Isella references rape and possibly human trafficking when she talks about “the beauty and the buyer,” a twisted version of the beauty and the beast. The “buyer” will “take the screaming one because / a woman who doesn’t want it is much hotter than one that does.” This claim that sex is “hotter” when it’s non-consensual is sickening, yet lies in an unfortunate societal truth some merit in our society — rape porn is extremely popular for both men and women. As kinky role-playing or acting, this is seen as acceptable, but the mere idea that a woman in distress is deemed “sexier” in our society is quite distressing.

After a refrain of two chants of the line, “Wife, whore, mistress, maid, mother,” which highlights the titles women are most often stuck with, we see a major turn in the narrative.

The speaker gasps before exclaiming, “The doll people are alive!” marking a turning point where the doll people demand to be seen as humans rather than mere art pieces or playthings. However, this breakthrough is short-lived, as Isella quickly adds: “Or so they say! / You can never trust / Never trust the art these days.” Her words shift the narrative back to the patriarchy, discrediting the doll people, with the famous line “or so they claim.”

The line, “You can never trust the art these days,” also recalls the #MeToo movement, when waves of women came forward with personal accounts of sexual harassment. As the movement grew, society began questioning the legitimacy of these testimonies, fearing an influx of false claims (since surely it couldn’t have happened to that many women). The phrase “these days” suggests a dismissive attitude, as if the surge of allegations were merely a passing trend rather than a long-overdue reckoning.

Another shift happens at the end of the song: “The doll people are gone / They don’t know what happened / They looked under our skirts one morning / but all they saw were maggots.” These lines are delivered with a mixture of sadness, concern and confusion. The conclusion for the doll people, however, is a strange, melancholic victory: “The dolls are off running and laughing together, / swimming in the milk of the moon.” The image of a milky white moon invokes thoughts of purity, femininity, fertility and immortality. Without women, of course, humanity could not go on. The doll people seem to have realized their power and have left the men to die out, choosing instead to reside amongst themselves and to live only for themselves.

“Cacao and Cocaine”

This last song on my list is a bit more upbeat, although it is still about the errors of human ways. It reminds me of a quote from Ursula K. LeGuin: “The trouble is that we have a bad habit […] of considering happiness as something rather stupid. Only pain is intellectual, only evil interesting.”

Basically, “Cacao and Cocaine” refers to the idea that society craves drama. Life is more interesting, the song says, if bad things are happening.

The song takes on an accusatory tone, asking the listener: “Would you like everyone around you to start screaming?” In a consumeristic culture obsessed with action, intrigue and horror movies, people have come to crave these things on TV and especially in real-life news. Have you ever noticed people’s obsessions with things like true crime, serial killers and natural disasters? Do you ever get a little rush reading the news? This song accuses everyone of wanting a little bit of chaos and pain in their lives to keep things interesting: a movie without conflict, after all, would be extremely dull.

Isella contrasts the two extremes when she says: “Would you prefer a brutal electrical shock / to sitting in a living room next to your thoughts? / Would you like your heart to get attacked? / Would that feel better than boredom in another beige and bland cul-de-sac?”

One of my favourite lines, which sums up the song pretty well, is: “Hand me peace on a plate, I send it back, I prefer pain!”

As if life is a movie to review, Isella asks: “Would you applaud the simulation, applaud the maker, / if you were constantly in the safety of danger?”

In a reference to people’s fascination with true crime shows and podcasts, the speaker admits: “I’m flirting with a boy that I think wants to murder me / I giggle, touch his hair, and wrap my fingers around my keys / I got over him in a few days, but I’m missing the thrill. I’ll put him in a case and take him like a happy pill.” The speaker admits that she willingly puts herself in danger to “feel the thrill” and perhaps to also feel like the main character. Bad things happen to the main character, but they always survive; they use their keys like a knife and they fight their way to victory and fame.

In an almost humorous turn, the speaker asks: “If Santa Claus came down your chimney with a machete / and told you to go get your will and casket ready, / would you go home at night thinking, ‘What a day!’? / Would you finally be entertained?”

Some of the final lines of the song, “Danger’s a slut, it’s in my gut, at night it whispers to me / […] ‘You want me bad, you want me back, but you don’t know what that means,’” emphasize our society’s misplaced desire for thrill and intrigue through danger, pain and suffering.

It must also be mentioned that the chorus is very catchy.

—

Honourable mentions from Sofia Isella include “All of Human Knowledge Made us Dumb,” a song about the internet; “Sex Concept,” which emphasizes people’s strange and backwards attractions; “Unattractive,” which talks about the unwanted male gaze; “Hot Gum,” Isella’s most popular song (which I find is very catchy but not as impactful); and “Rainbow Rocket Ride,” which is also a very catchy song that wasn’t provocative enough to make this list, but has a very cute music video.

She must also be commended for her disturbing visuals and occasional spoken poems such as “A Pen!s From Ohio,” “The Game” and “America’s Sweetheart” which is a satire on child actresses growing up (much to the disdain of viewers).

Sofia Isella is a completely underrated artist. With provocative feminist songs that somewhat resemble Melanie Martinez and Taylor Swift with an added edginess and a very dark tone, Sofia Isella deserves to be recognized for her lyrics, music and amazing voice.