Karl Marx’s central observation about capitalism was correct and the acknowledgement of that is desperately needed in a 21st century fraught with inequality and undemocratic institutions.

This whole writing year at The Brock Press I’ve been something of a broken record on the need to take socialism seriously as a political alternative to the dominant neoliberal consensus in the Western world. I’m not the only one, though. The Fraser Institute put out a poll that found socialism saw a favourability amongst Canadians aged 18-24 in the 50 per cent range. Needless to say, socialism is becoming favourable to younger generations—Gen Z and Millenials.

While the fear rightfully associated with names like Joseph Stalin, Mao Tse Tung and Pol Pot still plague and blossom into irrational reactionism in the generations that were most acutely subject to McCarthyism, younger people are realizing that socialism is just as diverse a tradition as any other ideology. Socialists of today are fairly sober minded when it comes to the failings of big 20th century projects. Many on the left today rightfully acknowledge that what the Stalinist USSR and Maoist China did was a kind of state capitalism that industrialized too fast and imploded from within. Demand always outpaced supply. That’s why the resurgent push for both top-down and bottom-up reform to capitalism from socialists like founding editor of Jacobin magazine, Bhaskar Sunkara, as seen in his book The Socialist Manifesto are so important.

Likewise, the Marxist economist Richard Wolff in his seminal work Democracy at Work argues that the worker cooperative is the way forward for the socialist movement in the 21st century and beyond. What a cooperative entails is the democratization of the workplace, where every worker has a share in the company and can vote on how the organization is run. The workers of an enterprise, then, are effectively their own directors instead of the division of owners and workers seen in traditional work organizations where the board of directors and CEOs, CFOs, etc. are the sole owners and pocket the profit created by the workers.

This would be the bottom-up aspect. The top-down aspect would no longer be the Central Committee as seen in the Soviet Union but institutional reforms in the state that would incentivize the democratization of the private workplace through preferential loans to worker co-ops or even through nationalizing banks, as well as rebuilding a progressive welfare state not unlike what one sees in the highly successful socialized models in the Scandinavian bloc. There’s also merit to the need for state control of the energy sector as it will be easier to facilitate a switch to renewable energy for the basic reason that the market mechanisms in place currently simply don’t address the climate crisis (which is criminally called an externality according to neoclassical economics).

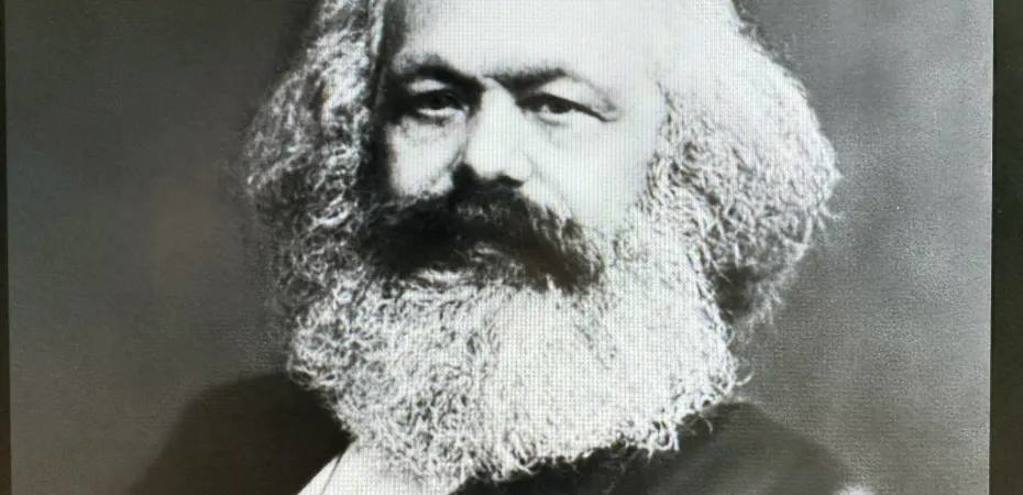

The common thread running through all of these arguments and proposals emerge from what was essential to Karl Marx’s study of capitalism as outlined in his masterwork Capital, released in Germany in 1867.

In the first volume of Capital Marx spends the first few chapters laying out his labour-theory-of-value (LTV). The LTV has been rejected by many economists and commentators since. However, the main idea articulated in it is still correct: workers produce commodities and capitalists sell them and pay back only part of the value created by the workers in the form of wages and hold onto the rest of the value — called surplus-value by Marx — in the form of profit. This is what Marx calls the exploitation of labour-power. And while Marx spends a great deal of time in Capital arithmetically tying the LTV into prices and other aspects of economic theory that appear to be a dubious gymnastics of universalization by today’s standards, the central idea of exploitation still stands regardless of if prices can or can’t be pinned down to a science that results from the socially necessary congealed labour-time of society.

What Marx made clear is that there is an antagonism at the heart of capitalism. The neoclassical approach has been to disavow this antagonism at every step of theorization. Key objections from the neoclassical side of the aisle include (I) that the capitalist takes a risk in starting an enterprise and that (II) the capitalist assembles the means of production (factories, tools, the workers, machines) in order to begin the production process in the first place. The first statement, however, is true of workers too. Workers have to sell their labour otherwise they risk homelessness and starvation; they too take a risk accepting to work for a company they have little to no control in because they have to to survive. To the second point, Marx already outlines how those means of production assembled by the capitalist are already congealed forms of labour from the past, a kind of frozen labour that Marx calls dead labour.

What labour-power in an economy does is it uses living labour from the living workers to create value with, on and through dead labour in the form of tools, buildings, machines, and even intellectual dead labour such as concepts. The capitalist is simply a mediator between the interaction between these two forms of labour that manages it but under capitalism he also takes the value created, claims it as his own, and apportions a bit of it through wages to workers so they can meet their subsistence requirements and continue to work for him. Capitalists ensure that they are not just mediators but owners and exploiters through the employee-employer contract which states in law that the employee agrees to sell their labour-power and, therefore, their muscles and brain to the employer for a wage.

The contractual aspect is why criticism of the state from the left shouldn’t focus on abolition first, as per anarchist thought, but on using state power to reconfigure this contract to a more just arrangement, again through preferential loans or by making wage and salary work illegal in the same way that paying under the minimum wage and sexually harassing employees is illegal. That would involve having a scaled form of penalization, starting at fines and ending with imprisonment. So no, the implementation of state sanctioned abolition of wage/salary labour doesn’t mean throwing capitalists in jail per se, just that there will be a sliding scale of punishments like when there’s other laws violated in the workplace.

It’s time to acknowledge that Marx was right and then work towards sublating the antagonism at the heart of the global capitalist system.