Score: 4/5

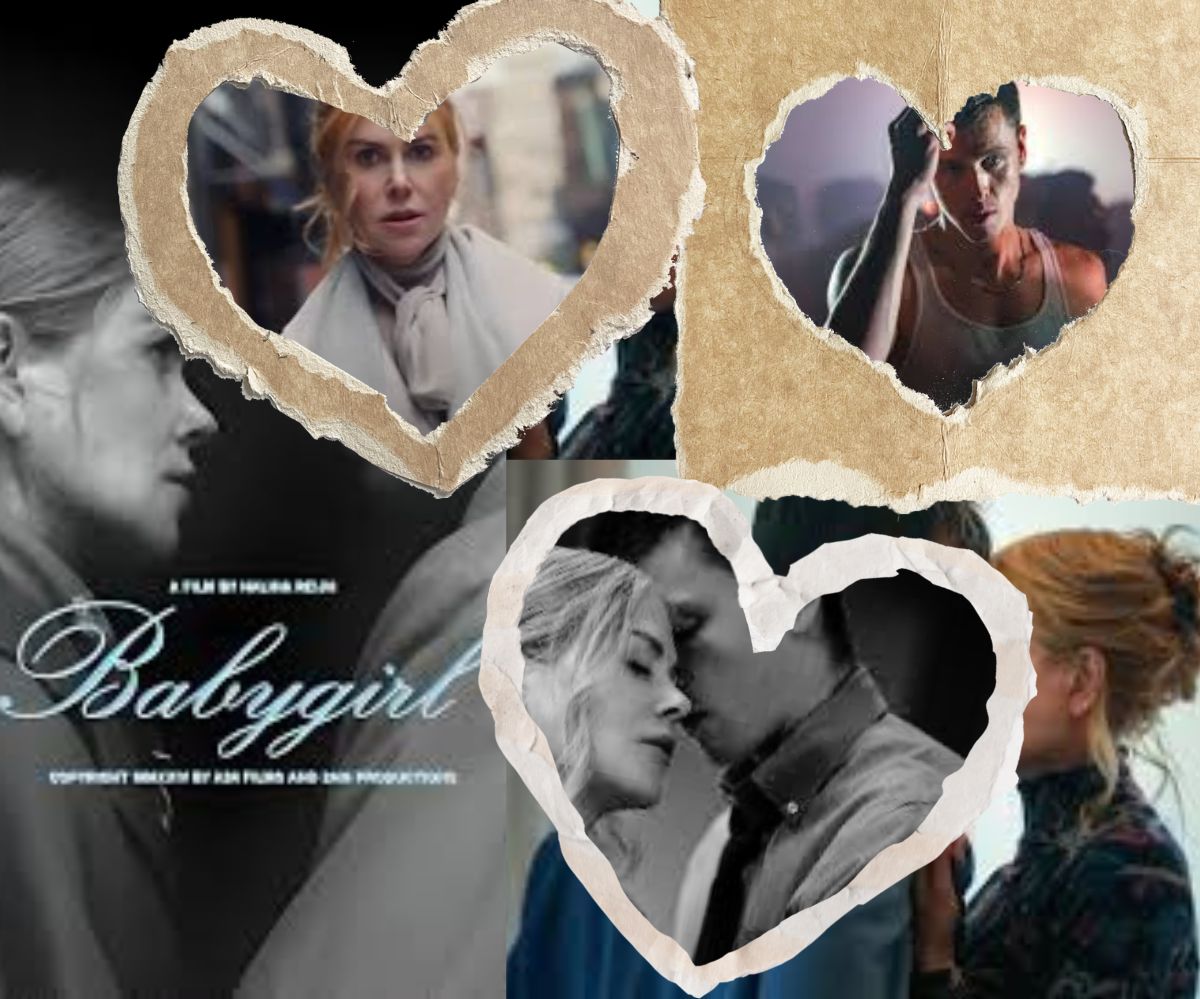

The latest film from Dutch filmmaker Halina Reijn is a hypnotic examination of power dynamics and a vulnerable exploration of sexuality.

The trailers for Babygirl set the film up for bizarre expectations. For one, it’s almost comically jarring to leap from a tame workplace montage with the festive Nutcracker theme playing to a secret kiss between a powerful CEO and her intern. In many ways, the film is everything you’d expect it to be and accomplishes what it sets up for itself, but it also challenges you to leave your expectations at the door. Babygirl evolves into something far more complex than what it begins as, never rewarding you with a cookie for thinking you have it all figured out.

Starring Nicole Kidman and Harris Dickinson, Babygirl is a clever film that leaves you scratching your head, but nonetheless entertained, inviting you back in to try to understand its peculiar rhythm.

Romy Mathis is a high-ranking CEO determined to maintain her position at the top. She is, and always has to be, in control of all areas of her professional and family life. On top of this, she is expected to be a powerful role-model for younger women seeking to climb the ranks and conquer the corporate world on their own.

She seemingly has it all together, having everything one could want in a sleek, sterilized, corporate dollhouse. However, beneath her calculated exterior lies a deep-rooted sexual frustration, a desire to blow it all up with her back turned to the flames. Her perfectly organized worldview changes upon meeting Samuel, an aloof intern far younger than her whom she begins an affair with, granting her the sexual satisfaction she’s longed for.

A film of this nature could easily feel exploitative if crafted by the wrong hands, but Reijn portrays sexuality with unflinching humanity that is as exciting as it is healing. Through the affair, Romy — and in turn the audience — are presented with the experience of recognizing one’s true wants and needs, removed from any constraints like social status, age or presentation. It’s cathartic and refreshing to watch sexuality written for the screen in such a humanizing and understanding way. No matter how scandalous the nature of the affair feels, there is a clear exploration of consent presented on screen that never feels preachy or removed from lived experiences.

Kidman achieves a stroke of acting brilliance here. It’s an odd performance to have in her filmography but is nonetheless an exciting addition to her work. It’s a performance that grants a steely control of her character’s world and subsequently, the freedom to portray total emotional vulnerability all at once. Looking at her work thus far, it’s fair to say Kidman has solidified herself as one of the greats, but films like Babygirl show she still makes exciting choices, taking bold chances on challenging roles that demand complete surrender and empathy. More often than not, her dedication to her work makes these moves pay off in her favour.

Where the film risks deflating its risky excitement is its third act, where the “lose-it-all-with-one-phone-call” level stakes feel removed from how the film solves its conflicts, which feels somewhat unrealistic. The conclusion is definitely rewarding and cathartic after you’ve journeyed alongside Romy, but it certainly retracts some of the “thrills” of its erotic thriller status.

That said, a film like Babygirl could not be more essential in this age of growing cultural conservatism, where the ironic, comedic condemnation of sexual exploration has seemingly circled back to an actual undoing of progress made in this area.