Advertisements are no longer reserved for billboards and television breaks. They are now hidden in almost every corner of media consumption online, and we’re not nearly as angry as we should be about it.

In the past, attempts to grab consumers’ attention were fairly obvious. It was easy to deduce that a company wanted your money when they bought 40 minutes of broadcasting time to force you to learn about their newest product via infomercial, raced to make a catchy jingle to stick in your head for hours after hearing it or plastered their company spokespeople on signs around town.

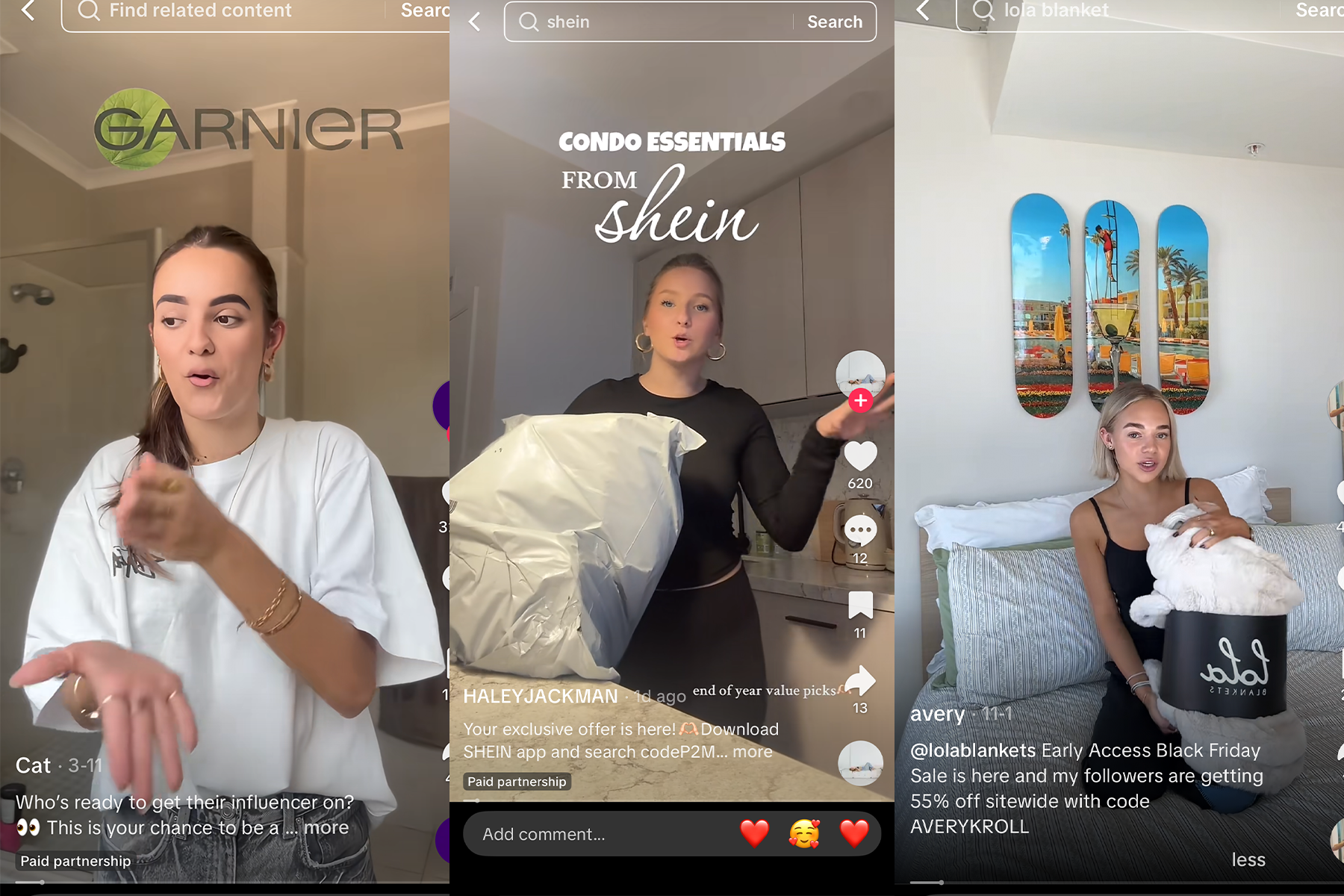

However, as we’ve moved deeper into the digital age, advertisers have become sneakier. Though many social media platforms legally require content creators to disclose when they are conducting a paid advertisement for a company, the way paid partnerships manifest in online content, especially short-form videos, can often blur the lines between an incentivized admiration of a product and an honest review — intentionally so.

Critically, short form videos with paid partnerships have the advantage of blending in with the endless content users can scroll through before and after said ad. Certain types of short form content are especially good at blending product placements into their videos, so much so that it often takes me about 15 seconds to realize that the Instagram reel or TikTok I am viewing is, in fact, an advertisement. These mediums include “get ready with me” (GRWM) content, wherein the content creator takes the viewer through their morning routines; “get unready with me” content, the opposite of GRWM videos, where the creator shows their daily wind-down routines; “outfit of the day” (OOTD) content, where the user shows where they got each item of their outfit from and, lastly, “day in the life” (DITL) content, where the creator brings the viewer with them for an average day of their life. DITL creators usually have specific occupations or lifestyles, including stay at home moms (SAHMs), students of various disciplines, professionals or those employed as influencers themselves.

The first three items in the above list — morning and nighttime routines as well as daily fashion content — centre around showing the viewer what products the creators use to make themselves look flawless a few minutes after waking up, foster coziness before going to sleep or how they encapsulate a popular online fashion aesthetic.

Despite the fact that these videos mainly function as unpaid ads, since the creator is directly encouraging anyone who wants to have a lifestyle like theirs to buy the products they use, I see that as less problematic with regard to the topic at hand. Though these videos contribute to overconsumption, they are more so rooted in genuine enjoyment of the product, since there is no direct profit incentive in raving about a product you like online (unless we consider influencers hopping on product bandwagons for views, thus having an indirect profit motive for including a popular commodity in their content).

However, ads slipping under the radar using short form content types — like the ones listed above — occur when the videos problematize creator authenticity and take advantage of viewers. Though users must disclose when they’re being paid to promote a product, this declaration does not necessarily have to be obvious. The declaration of paid partnership often comes in the form of tagging the video with “#ad” or noting that the creator “is partnering” with whatever company the product belongs to.

By blending a product placement into a content mode wherein the creator claims to bring the reader inside their genuine routines and real daily habits, the lines between authenticity and monetary motives are blurred.

The nature of algorithms further problematizes slick product placements. Since algorithms are known to consistently send users a plethora of content from creators that align with a user’s interests and perspectives, it is easy to deduce that someone who seems likeminded to you will be a more trustworthy figure. The parasocial trust given to influencers degrades user capacity to discern whether their favourite products are genuinely worth buying or just another monetization effort.

Though advertising has always felt manipulative, social media has made marketing worse than ever. Consumers should be angry that companies are skillfully slipping their advertisements into seemingly innocent social media content, profiting from users seeking a sliver of connection and relatability from creators they trust. I place more fault on the companies manufacturing the products advertised online rather than the creators themselves, as content creation can be an avenue to financial security for many, and unfortunately, product placements are a core way to generate income as a creator.

It is clear that the days of obvious marketing are gone. Instead, they’ve been replaced by subtle, exploitative tactics relying on manufactured authenticity and parasocial trust online.