In Latin American politics, it is no secret that the region has elected a great deal of left-wing governments since the dawn of the century. At the start of 2023 alone, 12 out of 19 economies in the region were managed by left-wing leaders, accounting for 90 per cent of Latin America’s GDP.

This trend in left-leaning governance, however, is increasingly challenged by a rise in populist far-right leadership.

While not entirely a phenomenon stemming from 2023 onwards, major shifts in governance have shaken up the region’s left-wing dominance.

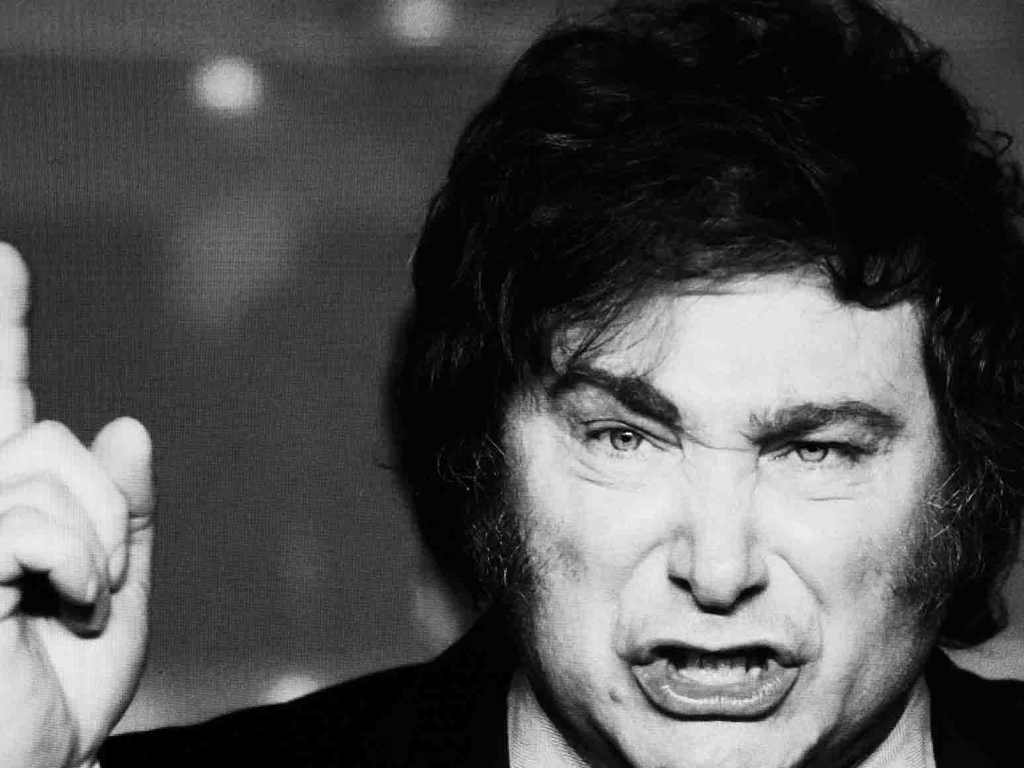

Perhaps most relevant has been the election of underdog candidate and self-proclaimed far-right libertarian, Javier Milei, in Argentina’s 2023 presidential election. Running on a campaign that denounced the left-wing government of former president Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, Milei borrowed from the political toolbox of successful far-right populists to promote anti-establishment and “anti-Kirchnerism”.

To add a layer of concern, the shift in the political paradigm of Argentine society was largely a youth-led effort, seeing as 70 per cent of young voters supported Milei’s presidency in the November elections.

As for the near future, certain outcomes are predicted to aid in the spread of far-right populism across Latin America, creating a concerning trend for governance and the maintenance of institutions in the region.

In the upcoming presidential elections in El Salvador, the authoritarian far-right incumbent Nayib Bukele is expected to be comfortably re-elected. With polls in late November revealing that over 93 per cent of the Salvadoran population will cast their votes for Bukele, the incumbent is virtually guaranteed a victory on Feb. 4th. That said, a legitimate concern exists for democracy in El Salvador as Bukele is running for re-election even though consecutive terms are considered unconstitutional.

Heading into an increasingly uncertain future for the democracies in Latin America, the rise of far-right populist leaders in the region represents a pendulum swing from left-wing dominance to an increasingly populist far-right landscape in Latin American politics.

Understanding Far-Right Populism

Notwithstanding that the term “populism” has been closely associated with the far-right ever since former U.S. President Donald Trump’s campaign and administration, it is essential to know that populism is not reserved for the far-right. Populism can manifest across the political spectrum and is often context-dependent on the region where it originates.

In alignment with the global backsliding of democratic values, right-wing populism is understood as a political ideology borrowing from far-right ideology and populist rhetoric and tactics for attracting popular support.

At large, this amalgamation of far-right thinking and populist speech encompasses anti-establishment thinking, posing as representative of the people and denouncing the “elite” class of scholars and public servants as the enemy. Furthermore, an “us” vs. “them” rhetoric is commonly employed to create a social divide and distinguish “the people” from public enemies like left-leaning candidates, leftist ideology, and in some regional contexts, immigrants.

The Latin American Context

As with most patterns in political science, far-right populism often takes on different elements depending on the regional or national context. In the case of Latin America, far-right populism is a relatively new development, although populist ideology has lingered in the region since the late 19th century.

“There’s a very long, deep history of populism in Latin America, probably more so than anywhere else in the world. What is interesting about Latin America and what kind of distinguishes it from most of the Western world is that the history of populism was usually, until recently, associated with the left.

“If you think of the 2000s and you think of populist leaders in Latin America, you would probably think of Hugo Chavez in Venezuela, Evo Morales in Bolivia and Rafael Correa in Ecuador, all leftists,” said Professor Pascal Lupien, Associate Professor of Political Science at Brock.

The prevalence of left-wing populism throughout the early 21st century, otherwise known as the “pink tide” in Latin American politics, was characterized by a regional rejection of the norms of the Washington Consensus and favouring of left-wing leaders, many of whom often were characterized as populist and authoritarian.

Approaching the 2010s, the partial undoing of the pink tide was representative of a collective rejection of corruption among left-wing populists and disillusionment with their governing post-commodities boom.

Notably, while the historical context of Latin America appears as a breeding ground for the proliferation of left-wing populism. The newly found interest in far-right populism breaks out of this paradigm of leftist populist governance due to global and local influences.

Globalization and U.S Influence on Latin America’s far-right

The increasingly globalized international community is not only interconnected in matters of trade and economics, even more so, the interconnectedness that exists serves to influence in matters of politics.

“Latin America is part of the broader world. Latin Americans are very connected, so they’re influenced by what is going on in the rest of the world, including the U.S and Western Europe and other parts of the world. But obviously with the emergence of Trump and the entire movement behind him, now the country is dominated by this type of politics, and Latin America has always been very influenced by the U.S in particular,” said Professor Lupien.

In recent history, the American, or more accurately, the Trump administration’s influence has taken Latin America by storm. For instance, Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil’s 38th president, elected in 2019 is said to have built his election campaign based on the success of Donald Trump’s political strategy. In following Trump’s formula for right-wing populism, the Bolsonaro administration emulated a “Brazil-first” approach, often attacking the left and identity politics in the process.

The most compelling parallel drawn between the Bolsonaro and Trump administration, however, was the anti-democratic uprisings in the Brazilian capital in support of Bolsonaro during the 2023 elections, where he lost the presidential race to Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva. Similar to the Jan. 6th Capitol insurrection in the United States, Bolsonaro supporters in Brazil stormed the presidential palace, Congress and the Supreme Court to call for the removal of Lula da Silva through military intervention.

Another character that draws comparison to former U.S president Donald Trump is Argentina’s newly elected president Javier Milei. Though Milei’s economic proposals are not identical to the economic measures proposed by either Trump or Bolsonaro, Milei’s anti-establishment rhetoric and wild takes on issues such as climate change often entangle him as a successor of Trump.

Fear, COVID and crime prevention

Though understanding the historical and global influences that have shaped a resurgence in far-right populism are practical, other factors are essential to understand this recent “blue” wave of far-right politics in Latin America. Primarily, the pandemic had unprecedented impacts on the already fragile socio-economic issues prevalent in the fabric of Latin American societies, exacerbating poverty, job insecurity and fear.

Simultaneously, the urgent material needs inherent to a post-COVID world have enabled crime to grow in the region, as poverty pushes certain areas of the population into organized crime as a means of survival.

“Right-wing populists in particular tend to do very well when things are going badly, because they certainly latch on to people’s fears and people’s anxiety about deteriorating economic conditions.

They also do very well when people are afraid when some kind of significant shift has happened that causes people to feel like they have lost control of their lives.

I think this has really been exacerbated by the COVID pandemic, which had a significant impact on Latin America, more so than here because so many people work in the informal economy,” said Professor Lupien.

In tangent with the economic anxieties created by the COVID pandemic, equally potent fear dominates crime-ridden societies, giving room for far-right populists to emerge or stay. In El Salvador, President Nayib Bukele has remained highly popular among the citizenry for his zero-tolerance approach to crime, enabled by the implementation of a state of emergency in the country which allowed authorities to arrest suspected gang members without due process.

Bukele is popular in the region for the increasingly punitive approach his government has taken for crime prevention, including the new “Terrorism Confinement Center”, a mega facility with a capacity for 40,000 inmates. Though a punitive approach is often celebrated by Salvadoreans, seeing as the homicide rate in the country has decreased by 92 per cent since 2015, the approach has raised human rights concerns.

In a report written by Amnesty International regarding the prevalence of human rights violations in El Salvador, the findings point out a weakening in the rule of law, violation of fundamental human rights during the state of emergency, and massive arbitrary detentions. Notably, though the criminal rate in El Salvador has decreased, the plausibility of this has only been guaranteed by state violence, promoted by populist far-right leader Nayib Bukele.

Though Latin American countries are not a political monolith, the newfound support across the region for far-right populism is gaining traction. It is to be expected that with the strength of globalization in an increasingly interconnected world, the influence of far-right populist leaders like Javier Milei and Nayib Bukele cannot be ignored throughout the region. As socio-economic conditions continue to worsen, and as long as fear of crime dominates Latin America’s consciousness, a large window of opportunity opens for new faces of far-right populism to emerge.