It’s not enough for well-intentioned leftists to simply express that capitalism is an exploitative and destructive system and expect change. The good news is that there are two major camps of thought within the Western socialist world with compelling visions for what an alternative economy could look like — the problem is these visions are at odds with each other.

Despite what intellectually lazy right-wing hacks in the media and online would have you believe, most serious socialist theorists and public intellectuals working today are not folks stuck in the 20th century with rose-coloured glasses for the Soviet Union’s and current-day China’s forms of authoritarian socialism (though, these types of scholars do unfortunately exist).

In fact, some of the most influential and interesting intra-left debates on alternative systems to capitalism in the modern Western world involve two novel theoretical camps on the subject. Moreover, both theoretical camps offer alternatives that firmly reject the authoritarianism embedded in the former Soviet Union and current Chinese economic systems while preserving the democratic essence of socialist thought. The main purveyors of both camps also suggest their alternatives would realize many or all of the benefits that utopian visions of socialism over a hundred years ago promised and failed to deliver on in the intervening decades.

The first of these theoretical camps argues that an economy based around worker co-operatives — firms that involve internal democracy — is the ideal economic-system alternative to capitalism.

The other camp, which broadly speaking can be called the democratic state-planning camp, argues that the Soviet Union and China did at least get right that state planning is the best way to allocate productive activity and needs-based distribution of goods and services in society. The shortcomings of these political-economic systems, they argue, can be traced to the eschewing with the necessary democratic mechanisms of elections and robust free-speech protections which are meant keep the state accountable. These democratic protections are especially important to stipulate, they argue, given a command economy is, in theory, more empowered than liberal democratic states given its dual monopoly on both force (police, military) and capital assets in society.

But before diving into the nitty-gritty of these camps of thought and their disagreements, let’s quickly go through what capitalism and socialism actually mean to better understand how these theoretical camps seek to rectify the former with a novel implementation of the latter.

—

Capitalism has been a slippery concept since the word came into common use a few hundred years ago. Many conflate capitalism with markets, or sometimes more specifically the free market (a dubious notion, if there ever was one). While markets are an important part of capitalism, they are not the defining feature of it.

Capitalism is fundamentally a system of private individuals owning the means of production in society — said means being everything used to produce goods and services for sale on the market: factories, buildings, land, machinery, tools, intellectual property and most importantly labour. Capitalists acquire ownership of these things through purchasing, inheriting or sometimes, though rarely ever the case these days, creating them themselves. In virtually all capitalist societies today, capitalist owners are legally entitled to the profit that they derive from the sale of the products their capital was used to produce.

Socialism is a reactive political-economic theory. Its reactionary component is to what its adherents perceive, at varying levels, to be the contradictions inherent to capitalism which cause all sorts of societal and ecological issues.

The intellectual tradition of socialism started in the 19th century — unsurprisingly around the time of the nascent industrial revolution in Western Europe — with a movement that later came to be called “utopian socialism.”

Utopian socialism involved thinkers who believed society could change through rational explanations about how communal ideals were the best ways to push society forward in a concertedly humanitarian effort to make life for every person better.

Interestingly, one of these formative socialist thinkers was a Welsh philanthropist named Robert Owen, a man who is considered the father of the worker co-operative socialist tradition. Owen even implemented his own experiments in co-operatively run communities in the United States, which he used his fortune to finance, but I digress.

The precepts of utopian socialism were quickly challenged in just a few decades’ time by other budding popular radical movements, foremost among them being anarchism and Marxism.

These two radical movements agreed with the utopian socialists that the rough setup of industrial capitalism needed to change in order to realize a more humane and equal society. However, they both criticized its naive belief that simply rationally arguing that their preferred reforms would be enough to make society more equal and humane would change the minds of the dominant classes — especially if such reforms meant necessarily attenuating some or even all of the latter’s power.

In contrast to the chimerical reformism of the utopian socialists, both anarchists and Marxists expressed that social revolution and class struggle often included tense struggle and even violence, and this had to be considered alongside reformism when pushing for the dismantling of systems of domination. This stark reality was something history attested to for these thinkers right up to the two then-contemporaneous violent outbursts born of class struggle at the time: The Revolutions of 1848 in Europe and the civil war to end slavery in the United States.

But it wasn’t all agreement between Marxists and anarchists. The two schools engaged in heated arguments, mainly centering around anarchists’ putting more focus on what they perceived as the greatest threat to liberty being state violence and Marxists placing in that spot the capitalist class, seeing capitalist’s domination of the working class and co-opting of the state for their private gain as a deeper threat than state violence itself.

Despite their disagreements, the two movements still both offered more realistic and rigorous approaches to creating a more equal society than their predecessors.

Now, anarchism notably isn’t a socialist ideology. Marxism, however, is a socialist ideology, and this is due to the immense influence that Karl Marx, in co-operation with his theoretical partner and patron Friedrich Engels, exerted on socialist thought with his voluminous writings.

A clear case of studious genius, Marx’s work was at the cutting edge of economics, philosophy and even certain forms of ethnography, historical analysis and statistics in the mid-late 19th century. By his death in 1883, socialism became synonymous to Marx’s writings, which is still somewhat the case today.

What was novel about Marx’s formulations of capitalism and socialism was that his analysis of the former in the three volumes of critical political-economic writing he produced, and which he ceremoniously titled Capital, deconstructed the capitalist system by using a strictly materialist lens of analysis. The work was and remains groundbreaking for its analysis expressly not relying on abstract or idealistic presuppositions in dealing with its object, as the text’s goal was to lay capitalism’s inner machinations bare and plain as it functioned in the concrete world. Included in such an approach was a commensurately materialist definition of capitalism, where Marx argues it’s a system of private ownership of the means of production with a genealogical-dialectical connection to past ownership systems involving an integral relationship between dominating and dominated classes that were all eventually toppled through class struggle.

This idiosyncratic definition of capitalism was nothing short of an aberration from much of the political-economic and liberal theory of the early enlightenment that preceded Marx. Said theory, from John Locke to Adam Smith, tended to inject a partisan idealism into its definitions and justifications for capitalist ownership rights.

While I won’t go into extensive details about the three volumes of Capital here (if interested, you can read my defense of the main theory of capitalist exploitation as laid out in the first volume of the work which I tackled in my last editorial), it’s important to keep in mind that Marx’s materialist philosophy meant that his visions of what socialism and communism will be, their being somewhat scattered and not amenable to a step-by-step program, as any Marxist scholar worth their salt will stress, at a bare minimum involved the satisfying of human needs and the abolition of unjustified and idolatrous class distinctions, both of which he saw capitalism as having.

Marx importantly noted, though, that capitalism often involves much repression of its idolatrous justification for class distinction from its partisans when compared to earlier major political-economic paradigms such as feudalism and slavery, the partisans and benefactors of which were more brazen about their dubious justifications for supposedly more “valuable” individuals who got to own things and people, sourcing such justifications from God and other divine hereditary sources.

Given the attitude of facing reality without any ideological repression justifying why class domination had to exist, Marx understandably placed great stress on outlining the condition of the working class under capitalism.

The working class, he argued, must coercively — coerced because if one doesn’t work, one starves — offer their much-needed labour to capitalists, and in turn see little more than an often-inadequate subsistence wage in return.

There’s no Disney ending to this story either, Marx would emphasize: the time workers spend toiling away for someone else’s private gain just to be able to survive will occupy the majority of what they spend their waking life doing before they die, taking time and energy away from family, romance, intellectual or physical self-development and importantly leisure — time to do whatever one wants free of responsibility.

Ultimately, Marx saw socialism as a system that acted to abolish the exploitation of the working class in the way capitalism does.

In such a system, instead of being hindered by the self-interested incentives of the capitalist class to expand their wealth and market share through exploiting labourers, society would centre basic human needs and the means necessary for everyone to enact the most self-actualization possible given their specific circumstances without impeding on the ability of others to do the same. Marx understood though, that there will always be intractable disparities in physical and mental ability, attractiveness and so on. To this, his famous “from each according to their abilities, to each according to their needs” dictum in The Communist Manifesto expressed an optimistic reframing of inherently unfixable ability disparities between individuals.

The dictatorial Soviet and Chinese socialist governments of the 20th century — and continuing into the 21st in the case of China — obviously didn’t accomplish Marx’s vision of communism all things considered.

In fact, in many ways these socialisms violated basic human freedoms to such a degree that, given the choice to pick, one would not easily be able to discern which position is worse between Marx’s Victorian-era industrial proletariat versus a collectivized farmer in either Maoist China or the early Soviet Union.

Now, there were some obvious gains that came with these experiments in socialism. Primary among them, first and foremost, was that both Russia and China’s communist revolutions led to the rapid industrialization of what were both previously rural and unmodernized agricultural-based countries. Second, there were some initial gains in personal liberties after the success of both revolutions, the granting of women’s suffrage in both examples being chief among them. With that said, many of these initial liberties would be rescinded in one form or another by both countries’ ruling governments as time went on.

—

Now that we’ve got a working definition of capitalism, socialism and some important historical context related to both out of the way, let’s return to our main focus of analytically comparing the the modern worker co-operative movement and the modern state-planning movement.

I’ll start by considering the respective pros of these competing ideas first, of which there are many. To do this, I’m going to take on what I consider to be the best formulated arguments from certain scholars and theorists that have been explicated from each side in recent times.

The case for a worker co-operative or WSDE economic system

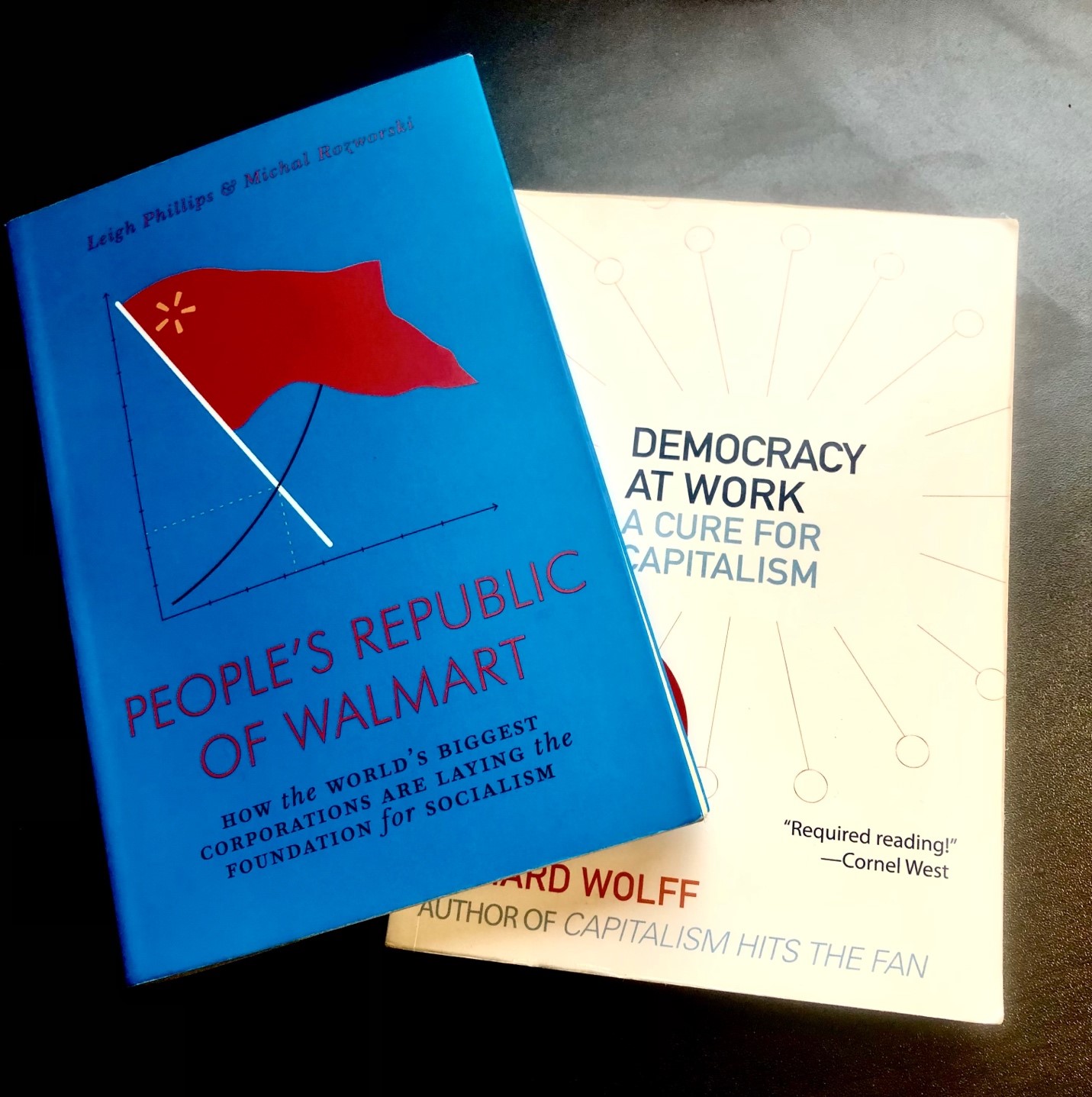

Professor Richard D. Wolff is easily the foremost economics scholar today arguing for a worker co-operative economy as an alternative economic system that will remedy the main societal ills that capitalism produces.

In his landmark text Democracy at Work: A Cure for Capitalism, released in 2012, Wolff puts forward nearly 200 pages — half manifesto, half treatise — arguing in favour of what he calls Worker Self-Directed Enterprises (WSDE). These are firms that, much like under traditional capitalism, own their own capital, but instead of the firm’s capital being owned by private individuals (bosses, shareholders, etc.), the capital of the firm is collectively owned by the workers within the organization. Therefore, workers in WSDEs are members who vote on things like who manages them and governs the workplace, pay-scales, what to produce and where to produce it, and all other major decisions a firm would face.

Much of Wolff’s argument in Democracy at Work focusses on Marx’s original theory of capitalist exploitation. He especially stresses the part of it describing surplus value as the creation of labour or labour-created machines, but which is undemocratically appropriated by capitalists who then, again undemocratically, pocket and reinvest the resulting profit.

Many readers will be familiar with consumer co-ops like credit unions or co-operative housing where membership includes a shareholder vote, members being those who consume the good or service of the corporation. WSDEs can be thought of as the flip side of a consumer co-operative arrangement: they are producer co-ops that feature a voting member base deemed as such by their producing the goods and services of the corporation.

WSDEs would necessarily remove the undemocratic aspect of private owners appropriating and having unilateral discretion over the surplus value that the other human beings in their enterprise — that is, workers — brought alive with their labour-power. Instead, in a WSDE, the workers of the firm would democratically appropriate and decide on what to do with the value they all played a part in creating.

This democratic process would reduce workplace exploitation — eliminating it fully in the strict Marxist sense of the word — strengthen employee-member protections against being arbitrarily fired, and create hierarchies within the workplace that are horizontally approved-on by those who are subject to them.

There’s also the potential for benefits beyond WSDE workers’ experiences at work. For example, there’s empirical evidence that, on average, those who are part of worker co-operatives feel more connected to their community (see George Cheney et al.’s Cooperatives at Work).

Furthermore, as Wolff references a few times in Democracy at Work, the largest worker co-operative organization in the world is a highly successful Spanish corporate conglomerate called Mondragon, which consists of tens of federated WSDEs.

Located in the Basque region of Spain, Mondragon has proven that WSDEs can be both production-intensive and competitively durable over the long-run, even when competing against traditional capitalist firms. It’s also been found that workers at Mondragon tend to report high levels of well-being. Such well-being is understandable given the instituting of progressive workplace policies at Mondragon like ratio caps on the allowed degree of gaps in remuneration between the least and most paid workers in the organization.

It’s also important to highlight that a WSDE-only economy would eliminate the system of wage labour.

Wage labour, mind you, is a contract between a private employer who hires an employee for the productive capacities of their body and mind for a certain amount of time in exchange for a wage that theoretically should be enough to cover the costs needed for that employee to sustain themselves and show up for the next shift. In other words, to reproduce their labour-power. The capitalist is incentivized to treat the wage as merely the cost of labour’s reproduction; the happiness of the human body and mind behind said labour isn’t necessary at all for capitalists.

In a WSDE, by contrast, the worker is a member rather than an employee, and so their compensation, while still necessarily needing to cover the costs needed to sustain their labour-power each day, importantly involves a share of ownership in the firm as represented in their vote. This has the effect of not having labour’s remuneration just be the cost of basic reproduction if it doesn’t need to be. Of course, competitive pressures and scarcity of resources are still things that can cause workers in a co-operative firm to mutually agree to depress wages to float the firm through a hard time, which was a decision made previously in the Mondragon corporation to weather the storm of an economic depression. However, if the corporation is doing well, the workers in a co-operative workplace have many means to increase wages beyond what’s necessary to afford a basic subsistence.

Wolff also emphasizes in the book and in much of his public talks on WSDEs that an advantage of a worker co-operative economy for society writ large is that the state has far fewer mechanisms to become like the Soviet Union or China, both of which he calls authoritarian state-capitalism.

Wolff argues that these past socialist systems were only nominally socialist because they weren’t democratic states, meaning they essentially replaced traditional capitalism’s undemocratic exploitation of workers with the state’s undemocratic exploitation of workers.

A WSDE economy on the other hand, while still needing to comply with state regulations on industry and the law like with capitalism, would de-couple and therefore decentralize capital-asset power from the state in stark contrast from the Soviet Union and China.

The case for a high-tech democratic state-planned economic system

As mentioned before, the opposing thought camp on an alternative socialist economy is one that is closer to agreeing with the premise behind the economies of the Soviet Union and China in that the state owns the means of production in society and plans all economic activity from top to bottom, what’s typically called a command economy. However, this camp adds a prerequisite that such a state must be a democratic one that allows elections as opposed to the authoritarian one-party rule seen with the CCP and the Bolsheviks.

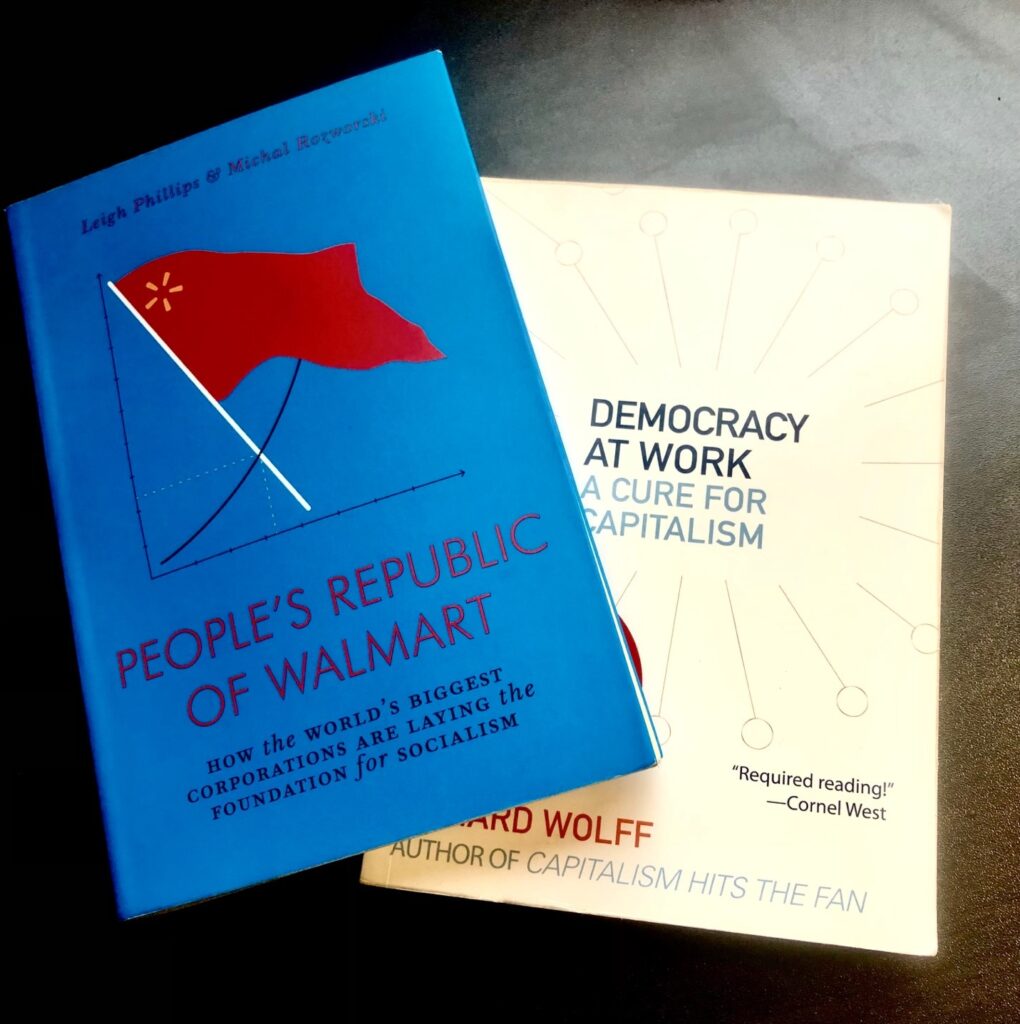

Easily the best and most-discussed work I’ve seen arguing for a democratic planned economy in recent years is Leigh Phillips and Michael Rozworski’s The People’s Republic of Walmart, released in 2019.

The crux of the authors’ argument for a planned economy in the book is that some of the largest corporations in the world — Amazon, Walmart, General Motors — are using today’s high-tech systems of data collection and processing in a way that’s completely planned from top to bottom. In doing so, these corporations are proving that nations, or even the world, could run highly efficient planned economies given that their internally planned economies have GDPs the size of actual countries.

The authors additionally point out that these corporations are in practice overcoming the famous 20th-century objection to planned economies that came from the influential Austrian economist and logician Ludwig von Mises, which was later expanded on by a circle of intellectuals he was a part of known as the Vienna Circle. This objection is known as the economic calculation problem (ECP).

The ECP argues that without price signals, planned economies cannot efficiently track and meet the subjective preferences of consumers as a sole centralized production agency simply cannot compute and act on the millions of market interactions taking place every minute in a national or global economy.

Phillips and Rozworski challenge that notion by finding a silver lining in the massive industries and technologies of today that capitalize on market demand through using the immediacy of information access that big data in an age of ubiquitous cloud computing allows for.

The authors therefore argue that if corporations like Amazon and Walmart can plan so effectively using the serendipitous technologies of today that track and package so much about consumers and their preferences to be able to efficiently plan production, storage and distribution of their products — then why can’t a government do the same but remove the need for commoditization?

Such a system would completely turn upside down the common association that people have with command economies producing wild inefficiencies that lead to disastrous famines and ridiculous wait times for basic products, issues that arose time and time again in 20th century socialist China and Russia.

Add on the democratic mechanism of elections to such a command economy made efficient by the powers implicit in modern advances in big tech and big data and you would have — in theory — a democratic socialism that meets everyone’s consumption needs, meaning class distinctions based on money and ownership would virtually disappear.

Arguments against each other

As I indicated at the outset, these two specific forms of socialism are mutually exclusive, the reason being that a worker co-operative economy retains market competition as firms, even if co-operatively owned by workers, would still need to compete with other worker co-op firms for market share to make profit. Alternatively, a fully planned command economy has no competing firms and no profit (barring the notion of a trade surplus in the global economy, but that doesn’t change this point in any meaningful way).

The core of this difference, therefore, lies in the distinction between the continued existence of the commodity form — a product produced to be sold on the market — as would be necessary in a worker co-op economy, and the disappearance of it, which would be necessary in a planned economy.

The most compelling arguments that the partisans of these theories levy at each other can be traced to this fundamental difference.

In fact, Phillips and Rozworski spend a small section of The People’s Republic of Walmart criticizing partisans of the idea of a worker co-op-based economy, which they refer to as market socialism. Key among their critiques is that doing away with private capital ownership doesn’t do away with the inherent problems of market competition and the commodity-form:

“…partisans of market socialism have to set aside the reality that the goods and services produced in markets, even socialist markets, will still only be those that can turn a profit. […] the set of things that are beneficial overlaps only in part with the set of things that are profitable. New classes of antibiotic, rural high-speed internet, and crewed spaceflight would all be as difficult to deliver under a socialist market as under a capitalist one, without significant, planned intervention into the market. Meanwhile, items that are profitable but actively harmful, such as fossil fuels, would still likely be produced.”

The authors also point out that the issue of market misalignment — the over- or undervaluation of market demand leading to mismatched supply — would still exist under market socialism given that competing firms would need to keep an informational firewall between each other in terms of aggregate demand data. In theory, the more demand-data synchronization in society’s productive sector, the less supply-side inefficiencies would exist. However, Phillips and Rozworski’s fully planned economy could, again, in theory, synchronize all the available aggregate demand information in society and subsequently gear targets for supply levels of production of goods and services based on that clearer picture of society’s total aggregate demand data.

Finally, the authors point to the former Yugoslavia’s socialist system that instituted something of a worker co-operative economy based on worker management of firms, still under partial control of the state the authors concede, as empirical proof of market socialism’s weaknesses related to marketization. They specifically reference how the problems brought on by market competition stoked the tension that led to the eventual separatist war and subsequent dissolution of the country.

Yugoslavia’s worker management system saw certain regions with more natural or pre-established capital than others, meaning firms competing with each other were not on fair footing. This problem led to pay discrepancies between workers and general inequality based on the regions Yugoslav workers were in. Consequently, such capital and income disparities enhanced regional rivalry, adding fuel to the eventual fire that was the ethno-nationalist war which tore the former socialist country apart, leading to over a hundred thousand deaths in its wake.

And while the Yugoslav government attempted to put capital taxes on more capital-intensive firms to control for discrepancies, this didn’t adequately alleviate issues of pay discrepancy and regional division (though, it should be noted that worker pay was far less divergent in Yugoslavia at the time than in Western liberal democratic nations).

Now, Professor Wolff does address Yugoslavia in Democracy at Work, but mainly to argue that the managers of the Yugoslavia worker co-ops, given their relations to the state, were just state capitalist managers and that it was through not having full-fledged worker owners that this system failed to fully alleviate exploitation and came apart.

Wolff’s engagement with Yugoslavia disappointingly doesn’t engage with how the issues inherent in the former socialist republic’s economic markets helped cause the eventual war; it’s simply not made clear in Wolff’s work how worker co-ops with no managerial pressures from the state wouldn’t still run into capital discrepancy issues, potentially causing societal tension and division, the former Yugoslavia being a pertinent example of this.

This makes the Yugoslavia example from Phillips and Rozworksi a strong point of criticism against worker co-operative enthusiasts.

Another issue related to the allowance of a market system and its need for certain government controls to combat inequality is that Wolff’s WSDEs should only — theoretically, at least — issue bonds or non-controlling stock options if they are public companies to preserve their status as being worker-owned. The exact degree of worker ownership necessary to make a worker co-op considered owned by the workers de jure, however, could become problematic if the there’s an effort to fully abolish a private capitalist class with worker co-operatives. If there’s no laws banning worker-co-op companies from issuing controlling shares to outside investors, issues around the existence of a capitalist class would likely persist, albeit in weaker forms.

For example, lacking such a law that fully bans controlling shares from outside investors, say some co-ops decide to offer up to 45 per cent ownership expressed in shares to outside investors as a shrewd tactic to acquire quick capital and get a leg up on their competitors. That company could theoretically argue that the majority share which workers have in being 55 per cent owners makes the co-op still worker-owned in some sense, causing a tricky debate on semantics.

It may even be plausible that workers would trade some or much of their control over the workplace in exchange for knowing that the advantages investor capital will give their firm in the short run are worth the long run losses of weakening worker control over the economy writ large. Issuing an enticing, but below 50 per cent, amount of controlling shares to investors could mean the short term, self-interested benefits of capturing more market share for the firm, benefits like higher pay for everyone, might outweigh the long-term downsides of allowing a private investor class to own large swaths of the private sector.

A final point against the co-op camp is that essential goods which can’t be administered effectively (read: humanitarianly) through markets such as education and healthcare would still have to be in the purview of the state. However, a market socialist economy could still see worker co-ops using their market power to try to grab a profitable slice of these necessary goods, just as capitalist firms do today when they prey on the edges of even universal healthcare systems, as is the case here in Canada.

On the co-operative side, though, there are arguments — again mostly stemming from that crucial difference of whether or not the commodity-form persists — that present solid criticisms of a fully planned economy that their side doesn’t have an issue with.

For starters, say a technological error occurs in a People’s Republic of Walmart-type economy causing the miscalculation of the demand for baby formula in a region, resulting in a massive shortage there. Inhabitants of that region that are in need of baby formula are then out of luck in terms of finding another vendor carrying what they need as there’s only the single provisioning entity of the state.

I don’t want to play a utilitarian game of whether such occasional misallocations in an otherwise smooth-functioning planned system is a better situation than the alternative in a market system where there likely will be other vendor options if there’s a shortage with one supplier, but with the trade-off that those who can’t afford said goods in the first place can’t acquire them (to be clear, I think the former is better so long as demand computing errors are occasional and never utterly catastrophic at a country or world scale). I will say, however, that it is a downside that the consequences of demand calculation errors in any type of fully planned economy will be orders of magnitude worse than under market socialism where there would likely be other vendors to choose from in the case that one or a few that consumers go to are lacking in supply.

Another issue, or at least an untheorized gap in a Walmart-type argument, is that if you stipulate that all the advanced technology of today overcomes the ECP and could be used for a fully planned economy, what would the basic unit(s) of demand quantization be absent prices?

I actually got into a back-and-forth with Leigh Phillips on X about this issue, and the agreement we landed on, while not unsatisfying, was somewhat lacking in a clear answer.

To summarize the essence of the contention our exchange was about: imagine being in the economic system that Phillips and Rozworski’s Walmart envisions. Assuming individual consumers submit requests through some state production agency website that looks something like Amazon’s UI, it would have to be the case that the number of requests would be the quantifiable basic unit of demand for goods and services that the state’s demand-processing technological apparatus would have to use to signal to its worker- and automation-based production systems in order to adequately supply the demanded level of production of certain goods and services.

That being said, an issue would arise if, say, a rare resource is a necessary input in a lifesaving medical device that is used to treat a rare disease that only a very slim part of the population has, but the same resource is a necessary input used in a very popular toy that many children in the same population really want.

In such a situation, the simple total number of requests for those different goods — the toy and the life-saving medical device — could not be equally weighted. The higher demand for the popular toy against the rareness of the disease would mean that those who need the life-saving treatment may not get it as a direct result of the toy’s popularity causing a bulk of the resource that’s needed as an input for both goods going towards producing toys given its much higher total demand level represented by requests.

When I was corresponding with Phillips on X about this hypothetical issue, a potential solution I suggested which Phillips positively responded to was that certain goods and services could be tiered based on necessity.

Basically, the more necessary a good or service, the higher the tier it’s in. Tiers could then be based on the size of a multiplier effect on the number of requests for any good or service within it.

So, going back to my hypothetical, let’s say that the life-saving medical device for the rare disease was deemed an A-tier good given its necessity to keeping people alive. Now, let’s say the popular toy was placed in D-tier because it’s just for kids to have fun with. A-tier would have something like a 1000x, or whatever number, multiplier effect on single requests to make sure the production of it takes precedence over the toy despite the difference in total single requests for the respective goods.

It could also be that tiers don’t confer multiplier effects on demand quantification and instead create an order for what should be produced first and foremost. Therefore, assuming they’re in different “importance” tiers, the highly popular toy would only be produced if the supply necessary to meet the demand for the higher tier medical device is produced first, regardless of the level of demand for it in total.

Even with these hypothetical fixes, the issue of how to deal with demand quantization of requests and their relative values would be no walk in the park.

And with this problem, political parties might even be grounded on philosophical differences in how requests should be weighed. If that’s the case, is it possible a populist party in such a system may argue that a tier system depriving many children’s happiness with a popular toy to save what will be a very small number of lives isn’t worth it, and that a compromise is needed where both get some of what they want in what would be another vertiginous utilitarian problematic? It’s hard to say.

The strongest criticism that co-operative partisans might issue against their planned economy counterparts, though, is that even if a fully planned economy has elections and the efficient allocation of goods that a high-tech apparatus of demand information processing grants a la Walmart, the dual monopoly that the state has on both violence, in terms of the military and police force, as well as on society’s total capital-assets could make an authoritarian ambition to subvert democracy easier as the ruling party of such a system would be more poised to leverage their sole discretion over the flow of goods and resources in attempting an authoritarian transition of one kind or another.

For the sake of argument, imagine a situation that has happened in the world too many times already: the high officials of a majority-power party make promises to the generals and chiefs of their military and police force that they will get privileged positions in the order of resource distribution if they help foment a military coup of the government. This scenario is made easier for a corrupt majority party in a fully planned system and more difficult in a worker co-operative system given the centralization of capital-assets in the government’s hands in the former and the decentralization and dispersal of them in the latter.

Barring a fascistic market-government alliance scenario, which usually requires an exogenous — or felt exogenous — threat anyways, a largely worker co-operative productive sector would require a government with authoritarian ambitions to engage in much more costly conflict if they want to gain control of capital-asset power through coerced or forced seizures.

The takeaway

Putting these novel socialist alternative models in discussion and debate with one another is not intended to reveal a clear “winner” after all things are considered.

If anything, I intended this analysis to be an incremental step in stimulating conversation and thoughtful engagement between what I see as the strongest formulated arguments for a socialist alternative to modern capitalism today. My hope is that doing so will help along efforts of solidifying the socialist left’s sense of what strong arguments we have to offer for an alternative to the existential threat that is the increasingly oligarchic techno-capitalism of today’s developed Western world.

One issue that many on the socialist left struggle with is that we tend to spend so much time in niche theoretical arguments, trying to figure out the perfect system alternative, that we forget just how marginalized we are in the current global political climate.

This is not to say that we should abandon the work of robustly thinking through and formulating economic alternatives down to the finest details at this moment. Suggesting that would be hypocritical for obvious reasons.

Rather, it’s to suggest that the approach to such thought and debate needs to embrace disagreement in order to — to use an often frivolously thrown around term in leftist theoretical spaces — dialectically engage with the differences in arguments put forward.

If this piece is intended to have a takeaway, I’m hoping it’s that the socialist left has two strong arguments on our side that aren’t just lazy attempts to white-wash or ignore the authoritarian excesses of the socialist states that have existed and continue to.

However, these arguments evidently do expose, implicitly and explicitly, important weaknesses or gaps in the foundations of each other’s theoretical architecture which will need work.

Photo by Haytham Nawaz